I’ll start right out with an apology. I hope you haven’t come here in hopes of seeing some nice, organized, highly annotated portfolio. That it is not. I don’t have the enthusiasm to curate my old stuff. It’s really more of a repository—a dump, if you prefer—of the last twenty-odd years of my work. Anything before that has been deleted from the Syquest of Time. And it’s nothing but one long scroll. No categories, no timeline, no menus, no search. So apologies.

If you want to get in touch, email me.

Happy scrolling.

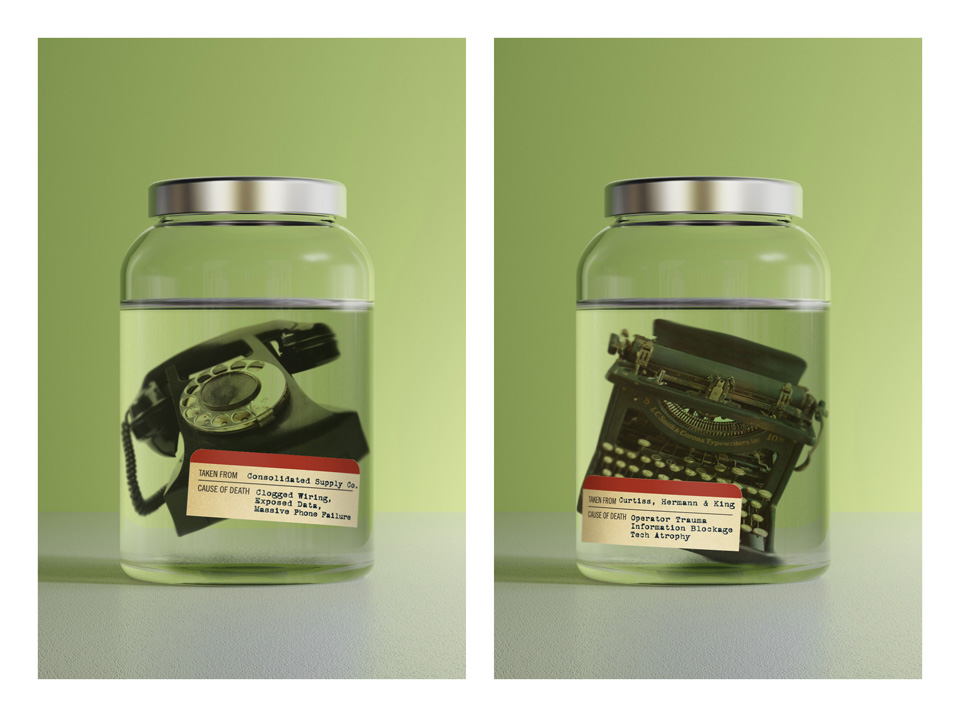

I have been doing what I do for a very long time. So long, in fact, that when I first took it up, and for many years after that, it was a literal handicraft. Our only tools were typewriters and knives and adhesives and rulers and sheets of film and endlessly frustrating ink pens. Mind you, big-wave surfing into The Future, where we could lay down our xactos and power down the stat cameras and do no more work with our hands than pointing and clicking in a tiny, tiny space on our newly-tidy desk and basically making the page look however the hell we wanted it to look was exhilarating and freeing, don’t get me wrong. But the expansion of the creative possibilities silicon made possible came at some meaningful loss of many, many venerable trades, and in my dottage, I’ve been mourning them. So lift a pint to the typesetters and pasteup artists and color separators and camera operators and strippers and platemakers. And raise another to marker comps and layout boards and proportion wheels and Daige wax and Bestine rubber cement and Rubylith and Letraset and 000 Rapidographs and cutting apart words of nine-fucking-point type with a #11 blade. (I am preparing what will be The Most Boring TED Talk Ever; watch your YouTube.)

If there’s anything to be gleaned from all this chaff, if I was asked to pass on one—very brief—summation of fifty years of practising this trade disguised as wisdom, it would be this:

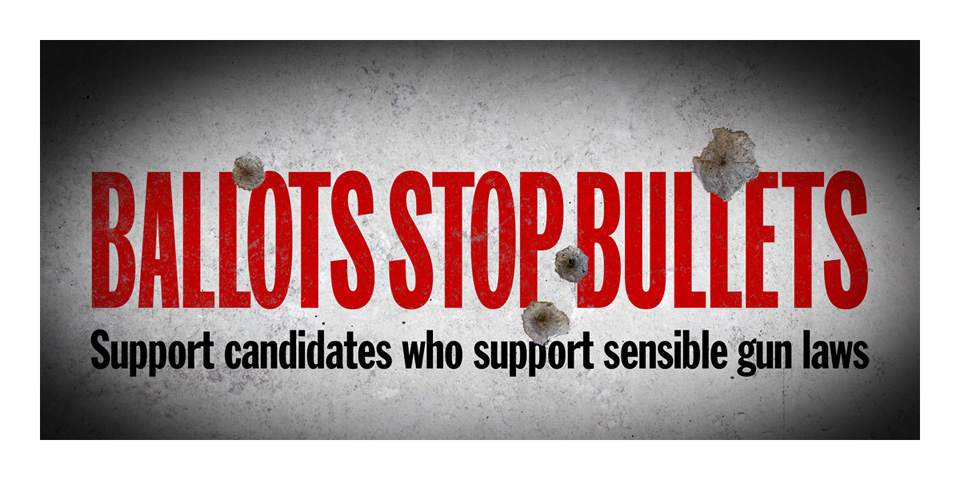

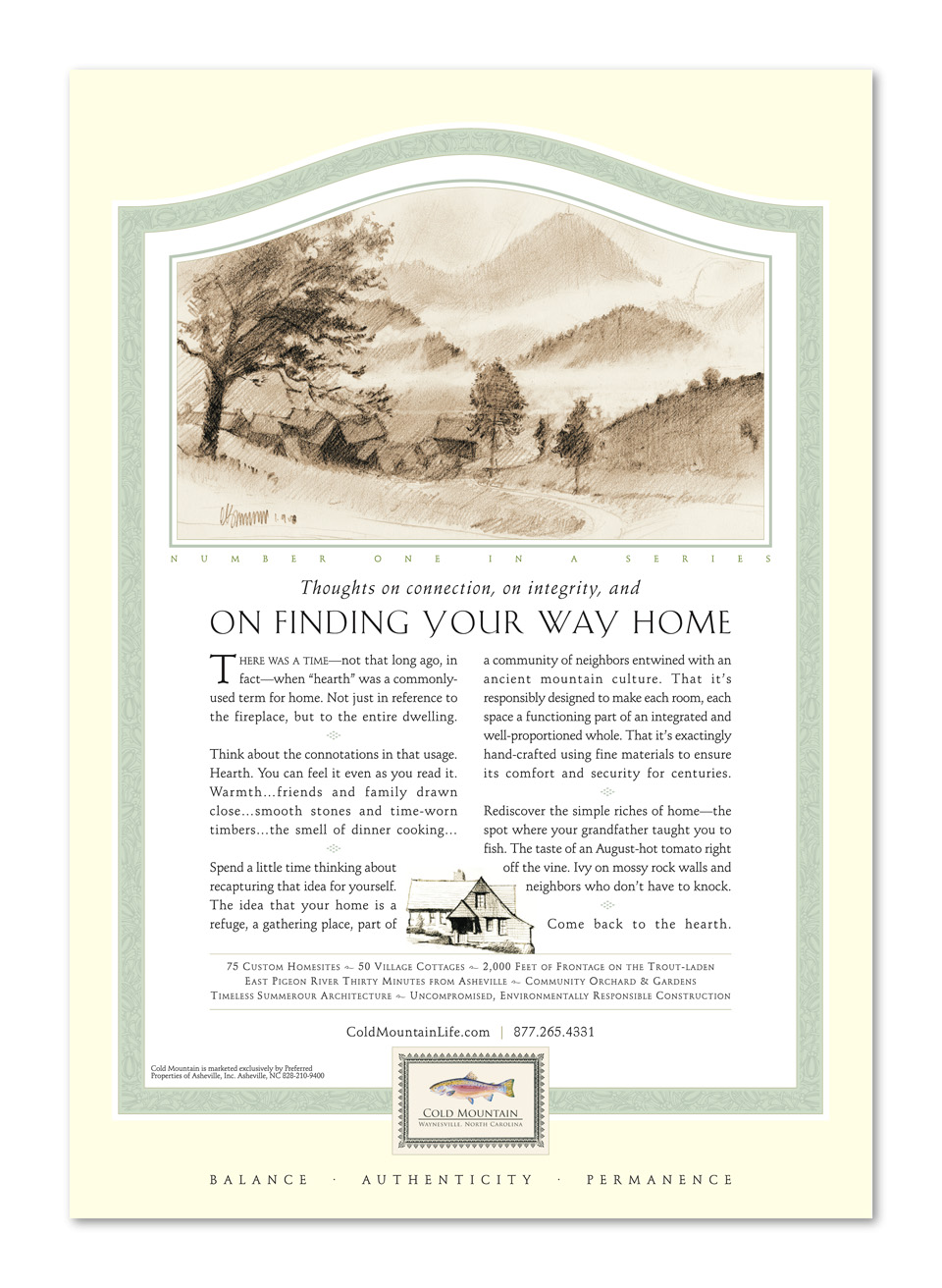

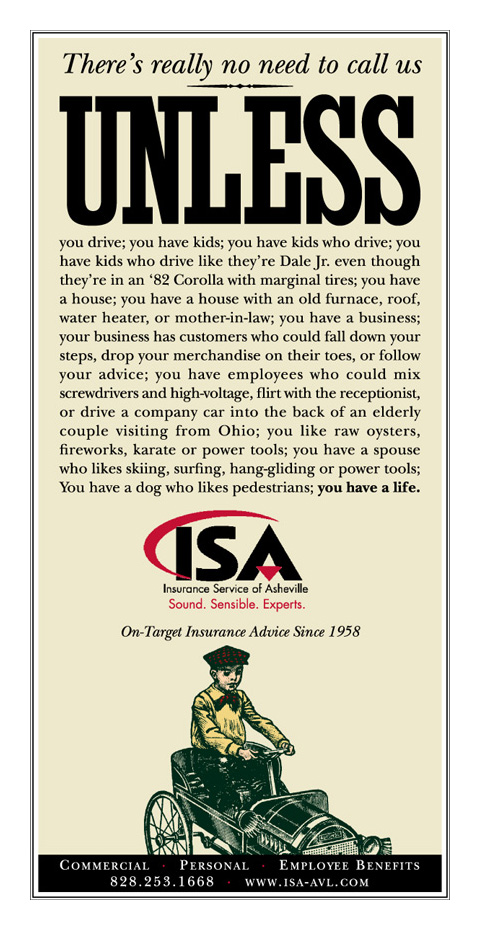

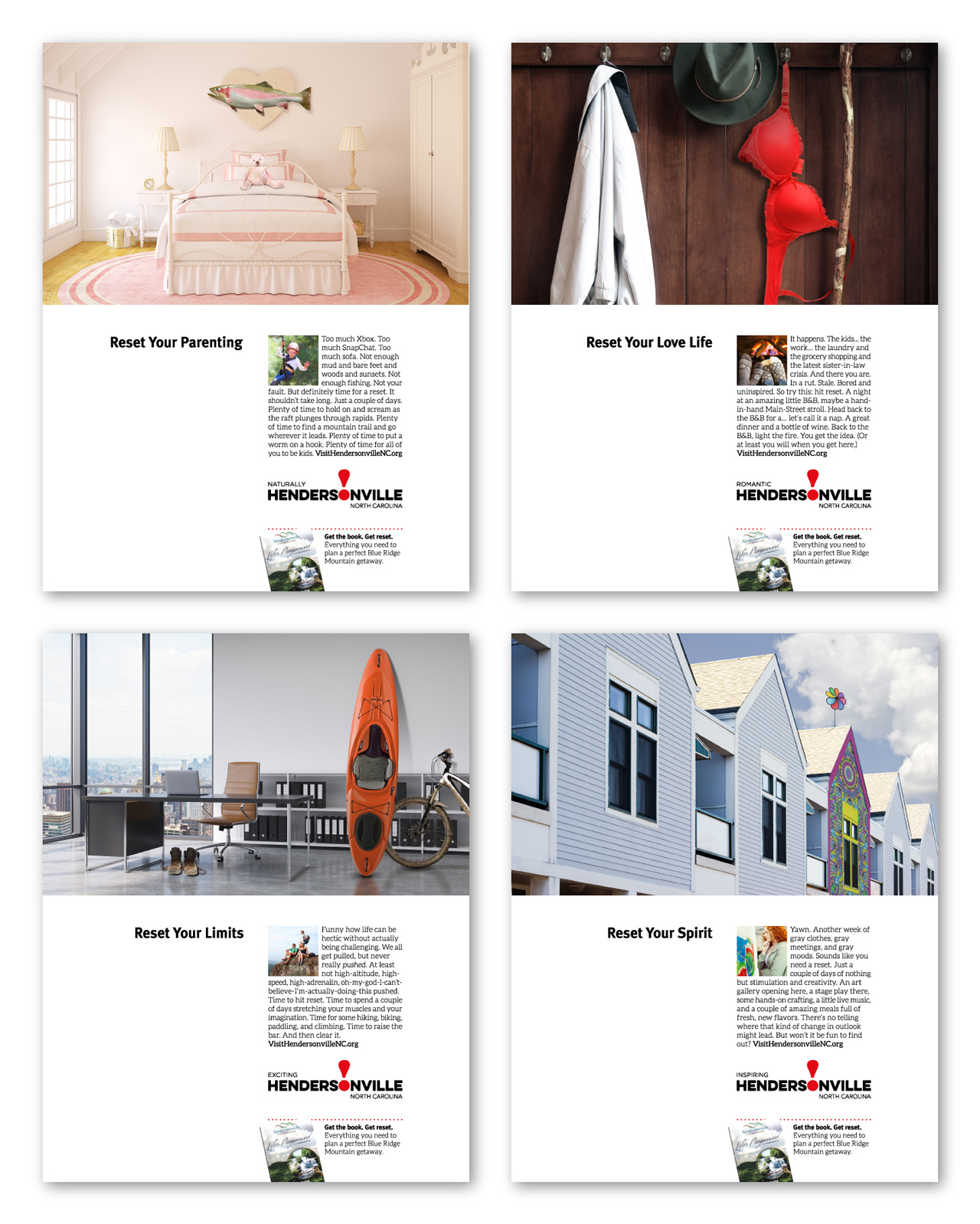

You’re going to be spending a lot of money to say something, so go on and say it.

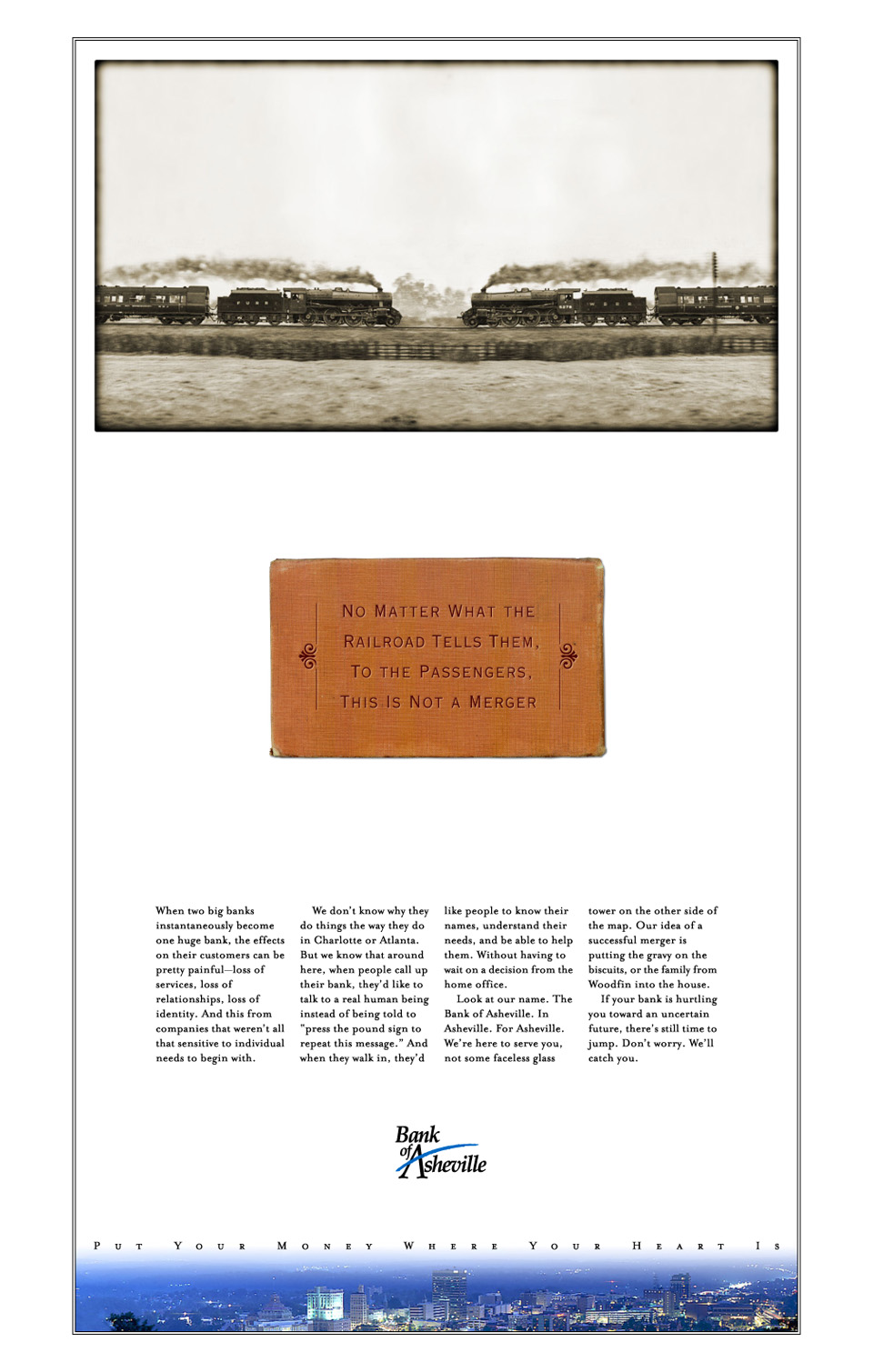

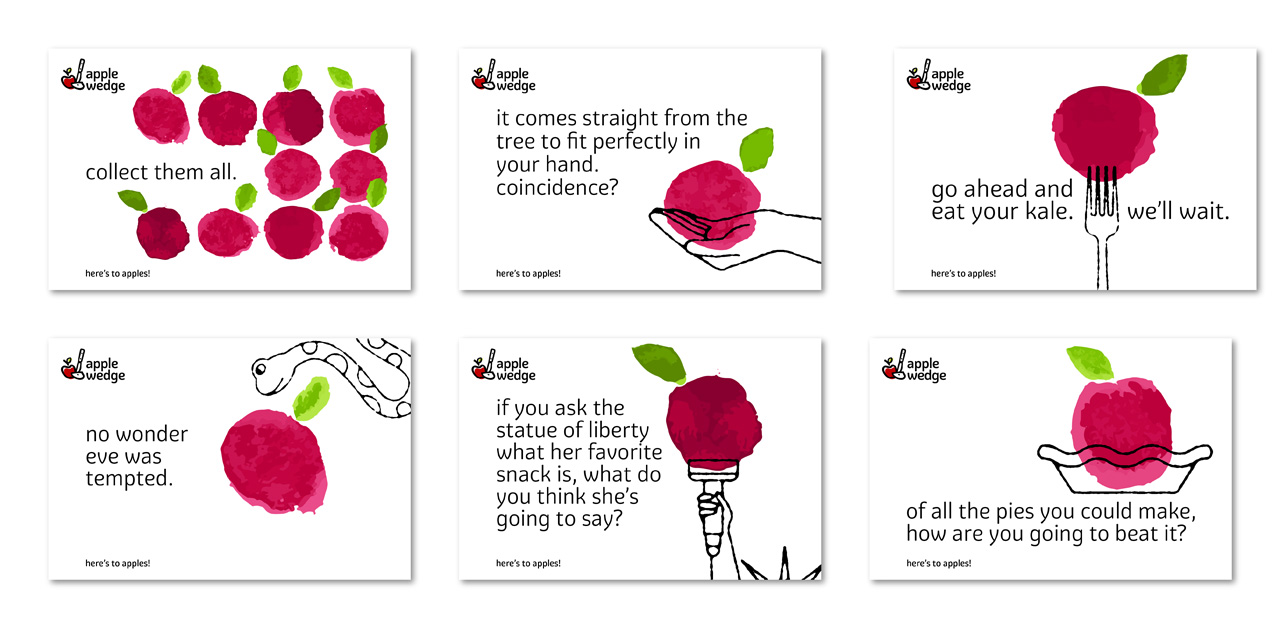

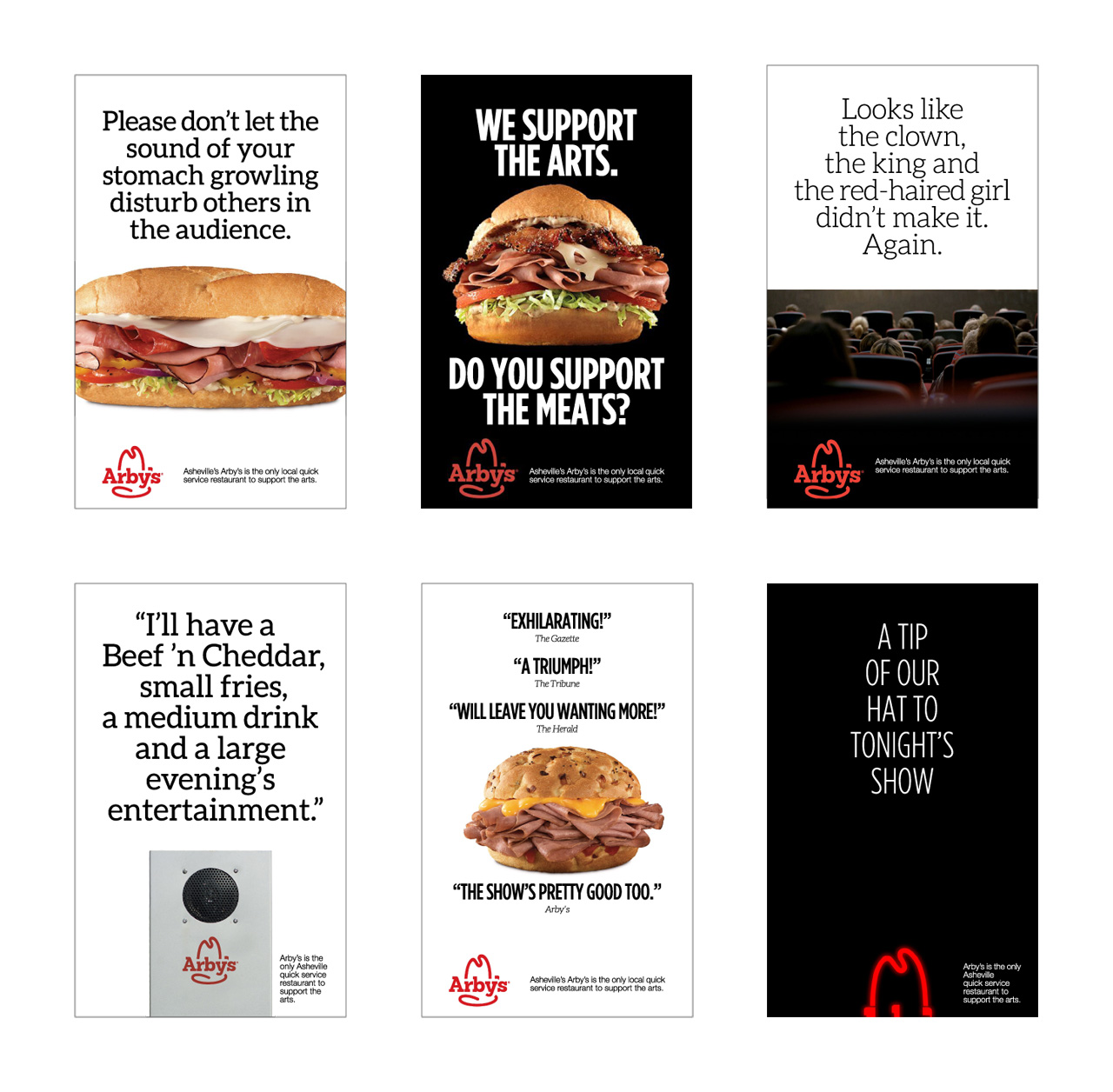

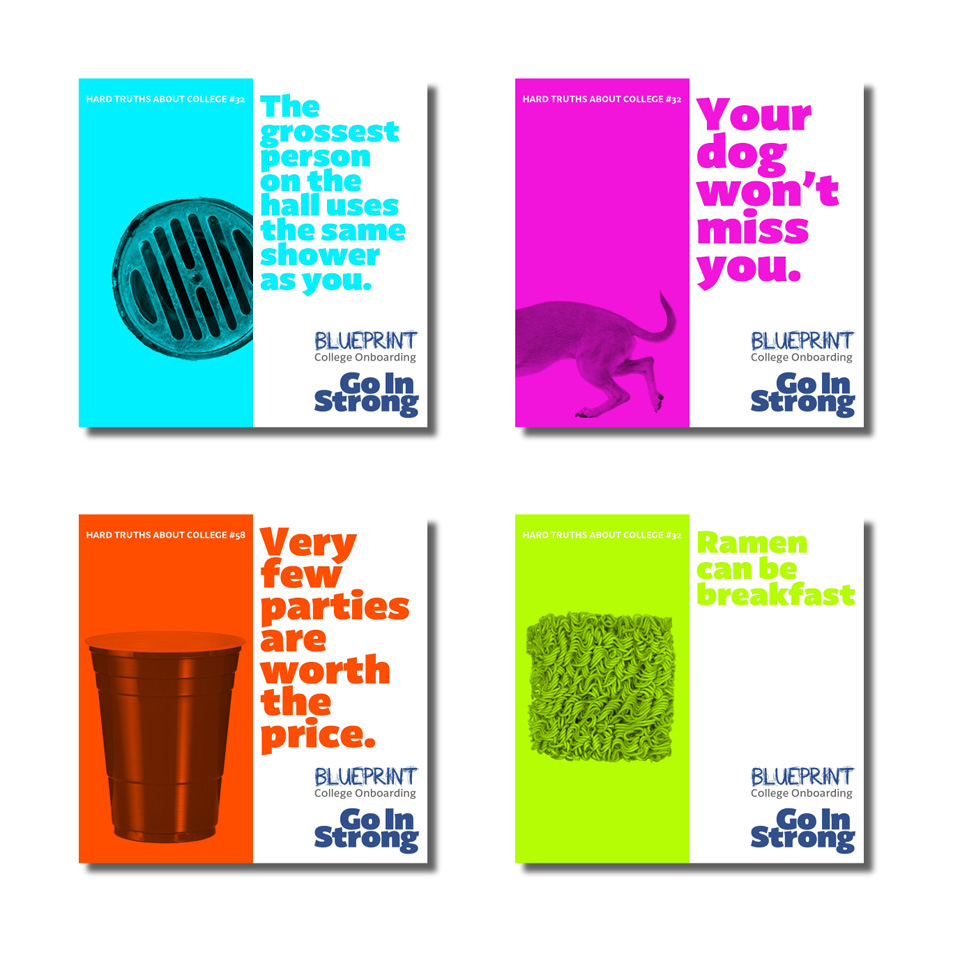

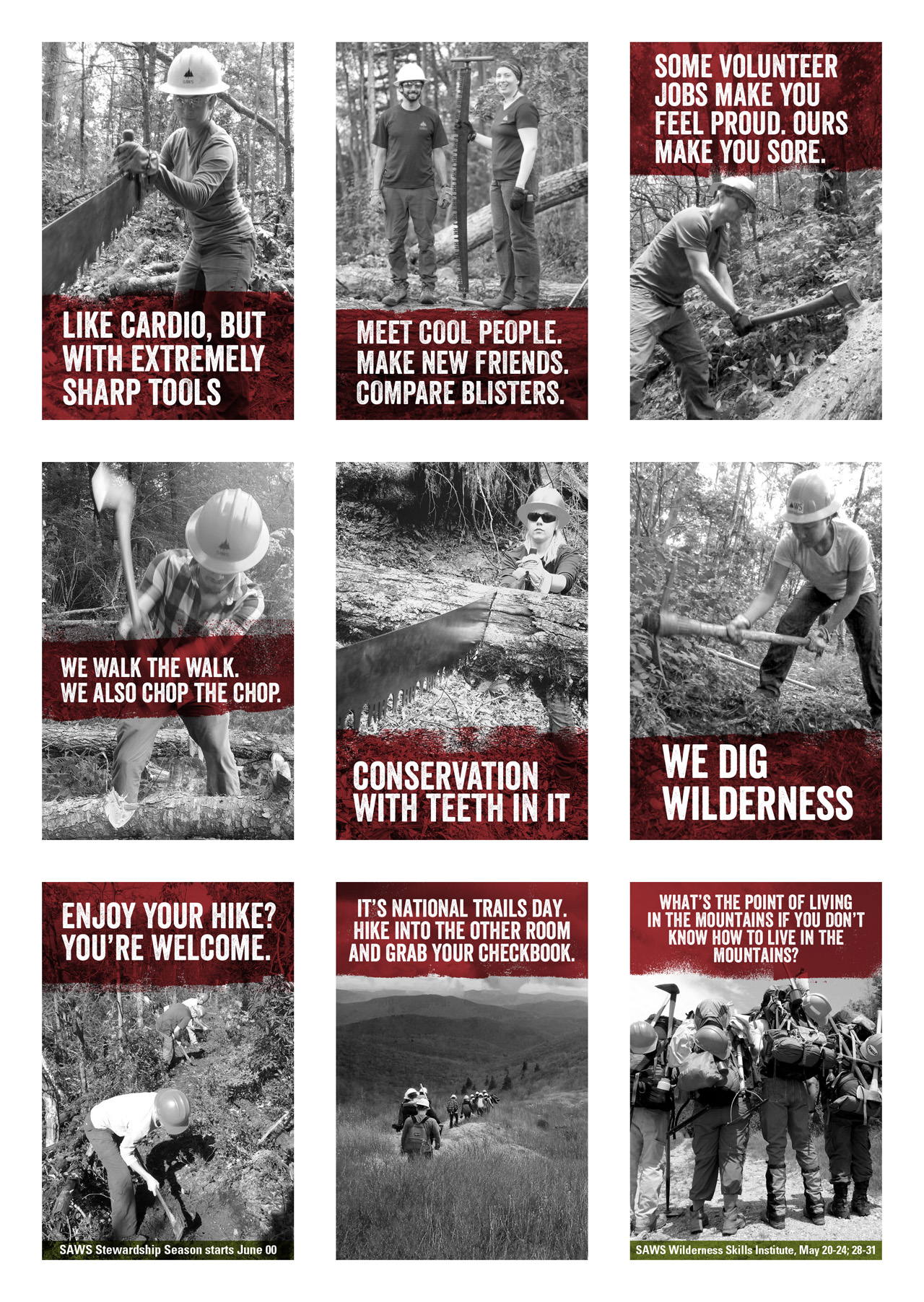

You have to make people want to hear you even though they’d rather not. Like if you were at some swanky party (I imagine—I don’t get invited to swanky parties) and you spotted a cluster of cool-looking people and so you insinuate yourself a little closer. Close enough to catch bits of conversation. And what you hear convinces you that you want to join these people in stimulating repartee. To succeed at this, you better go in with Dorothy Parker on one arm and Tig Notaro on the other. Because if you bust in with “Anybody here watch The Office? Wow, right?” you will be mercilessly ignored.

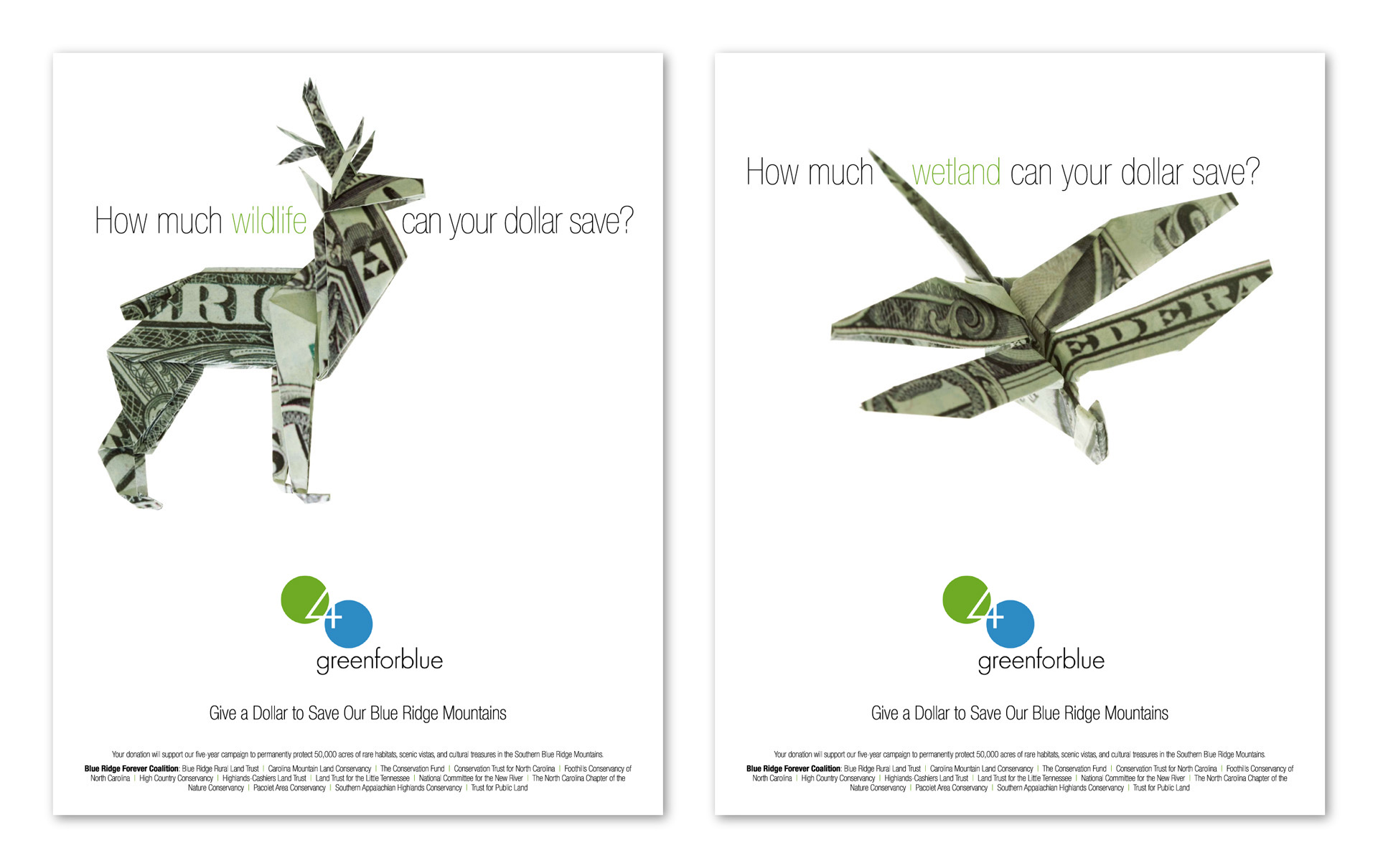

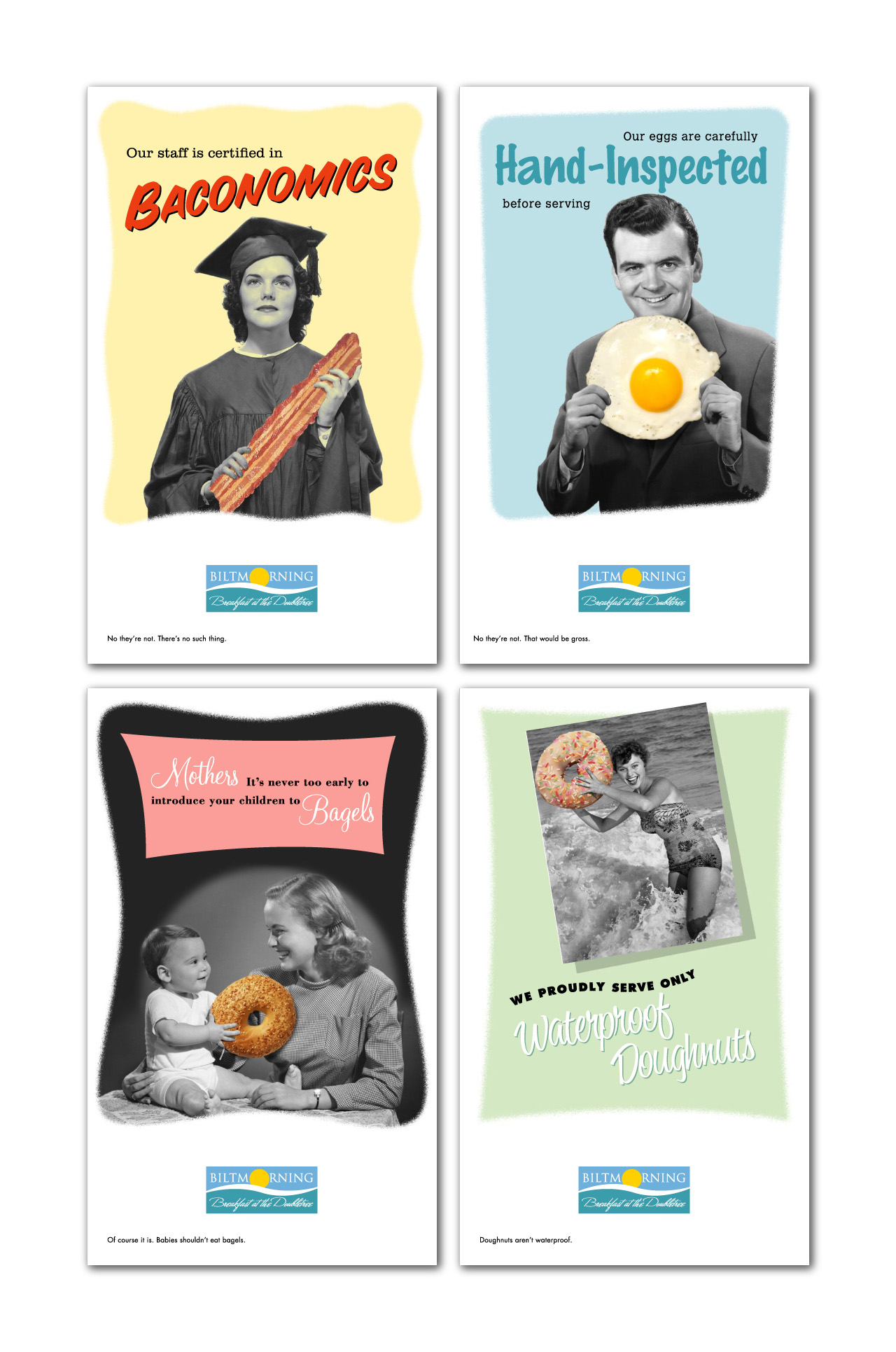

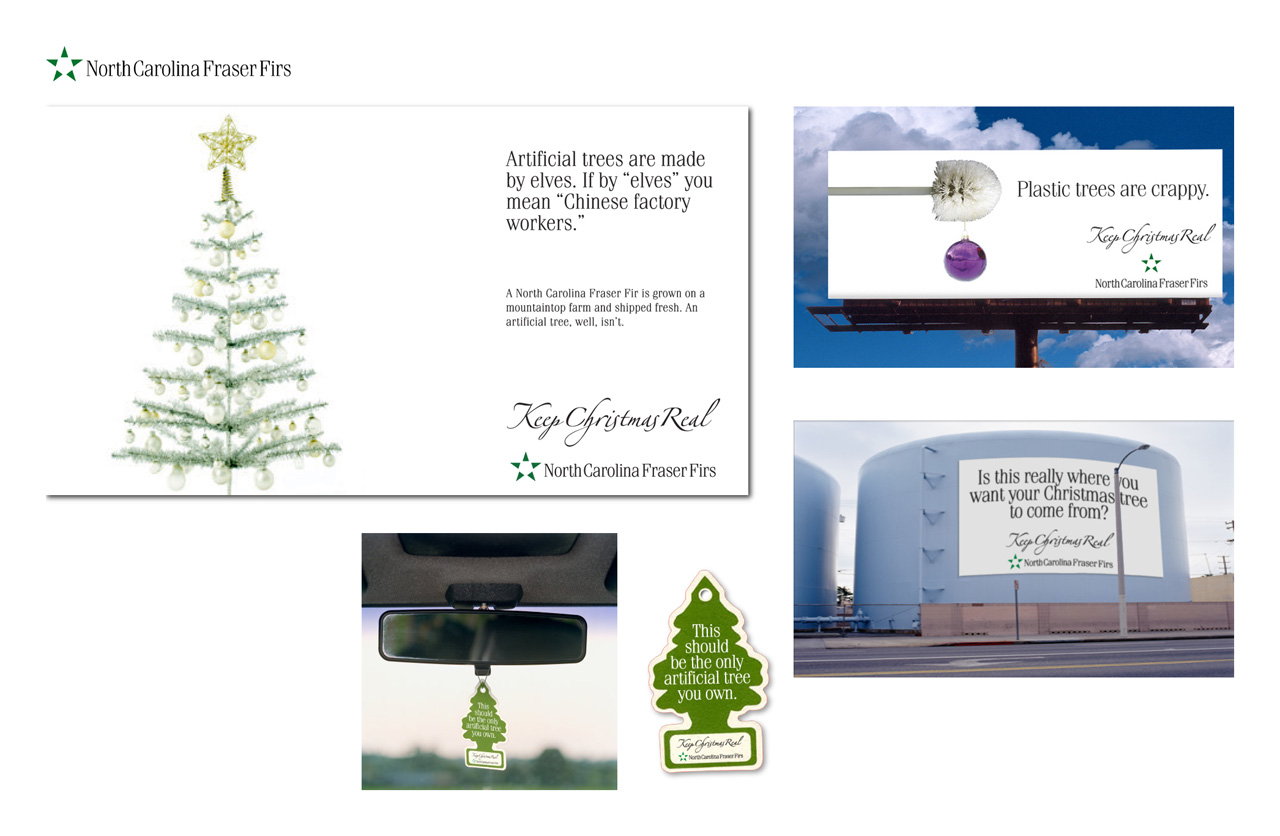

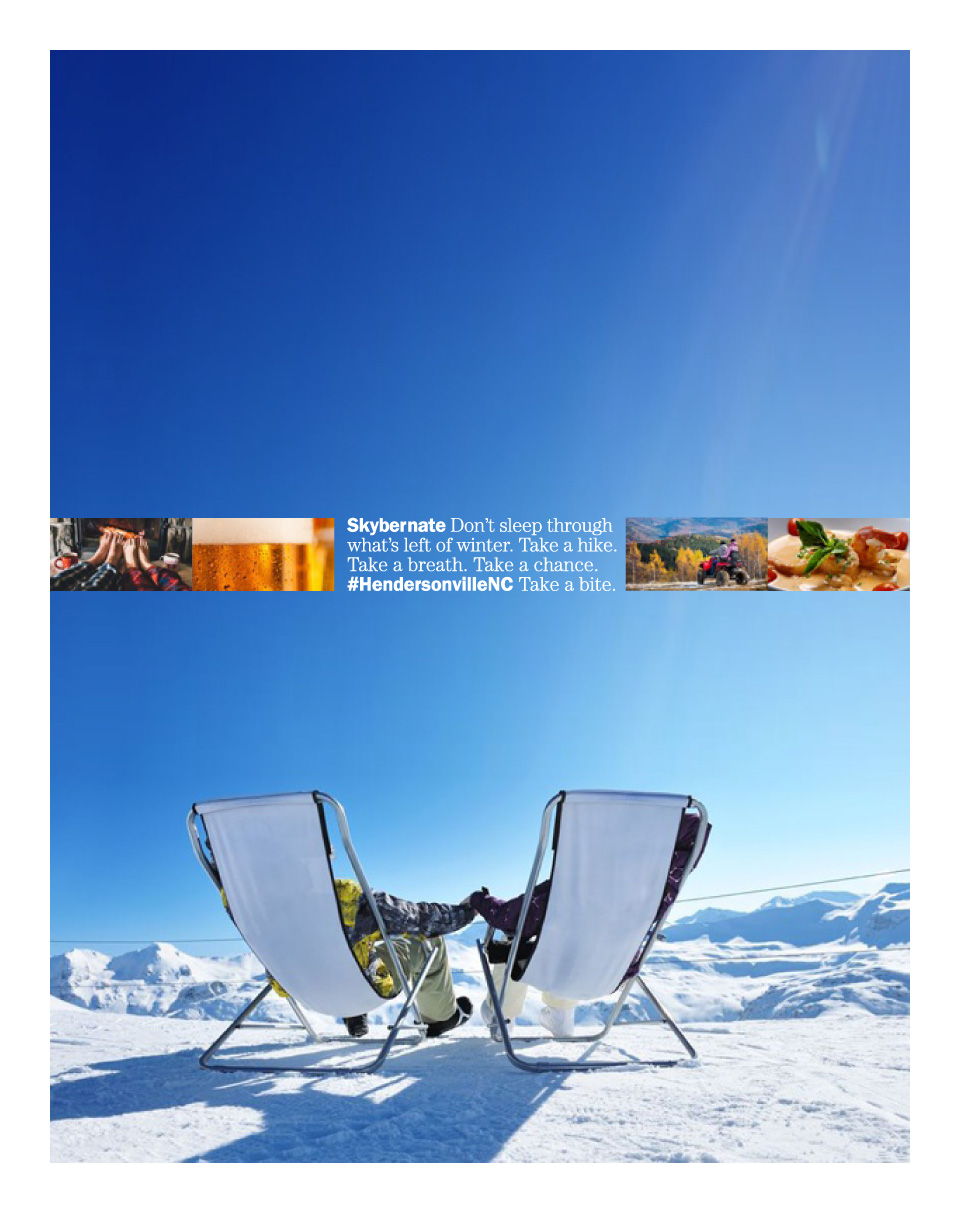

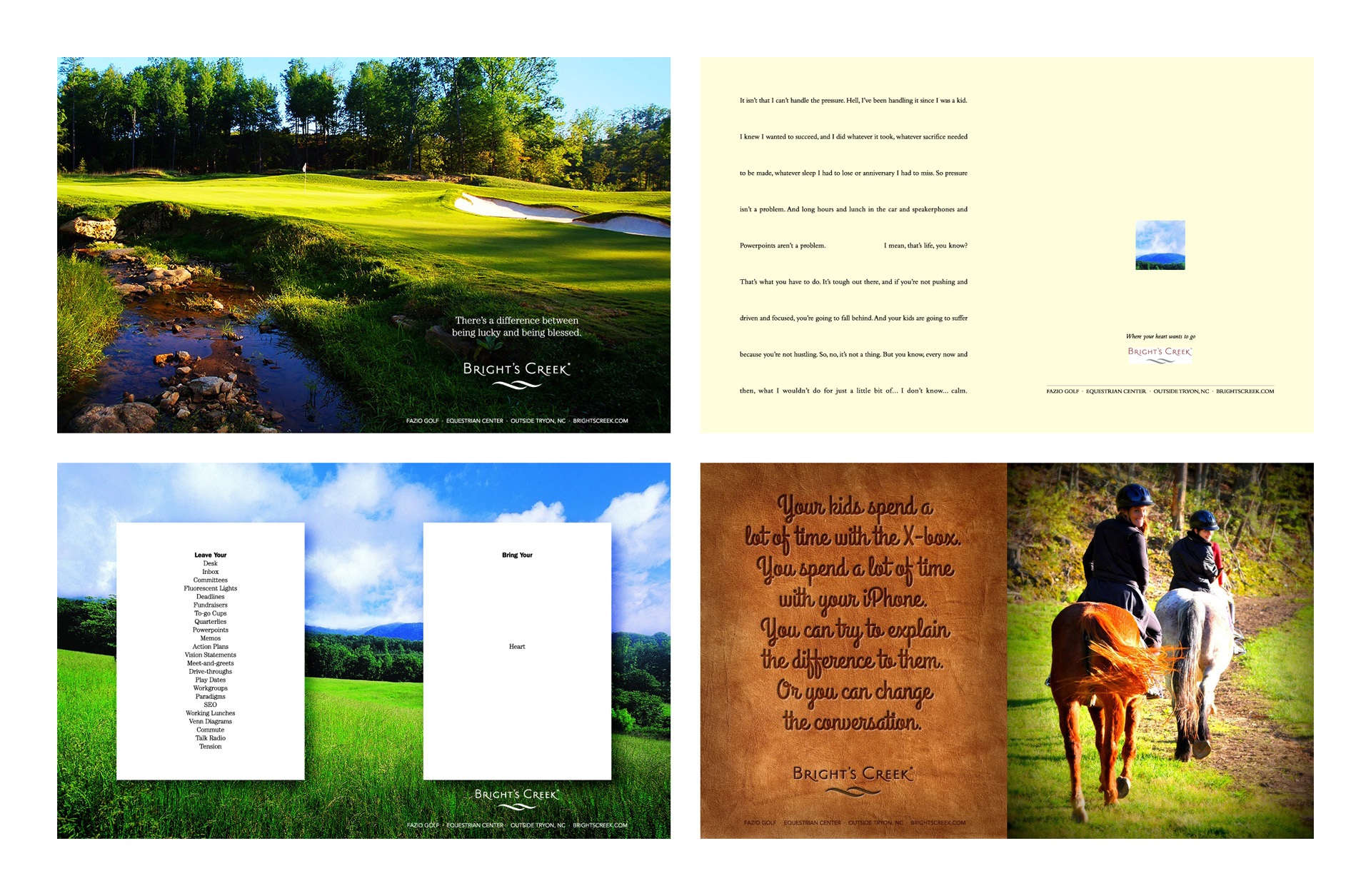

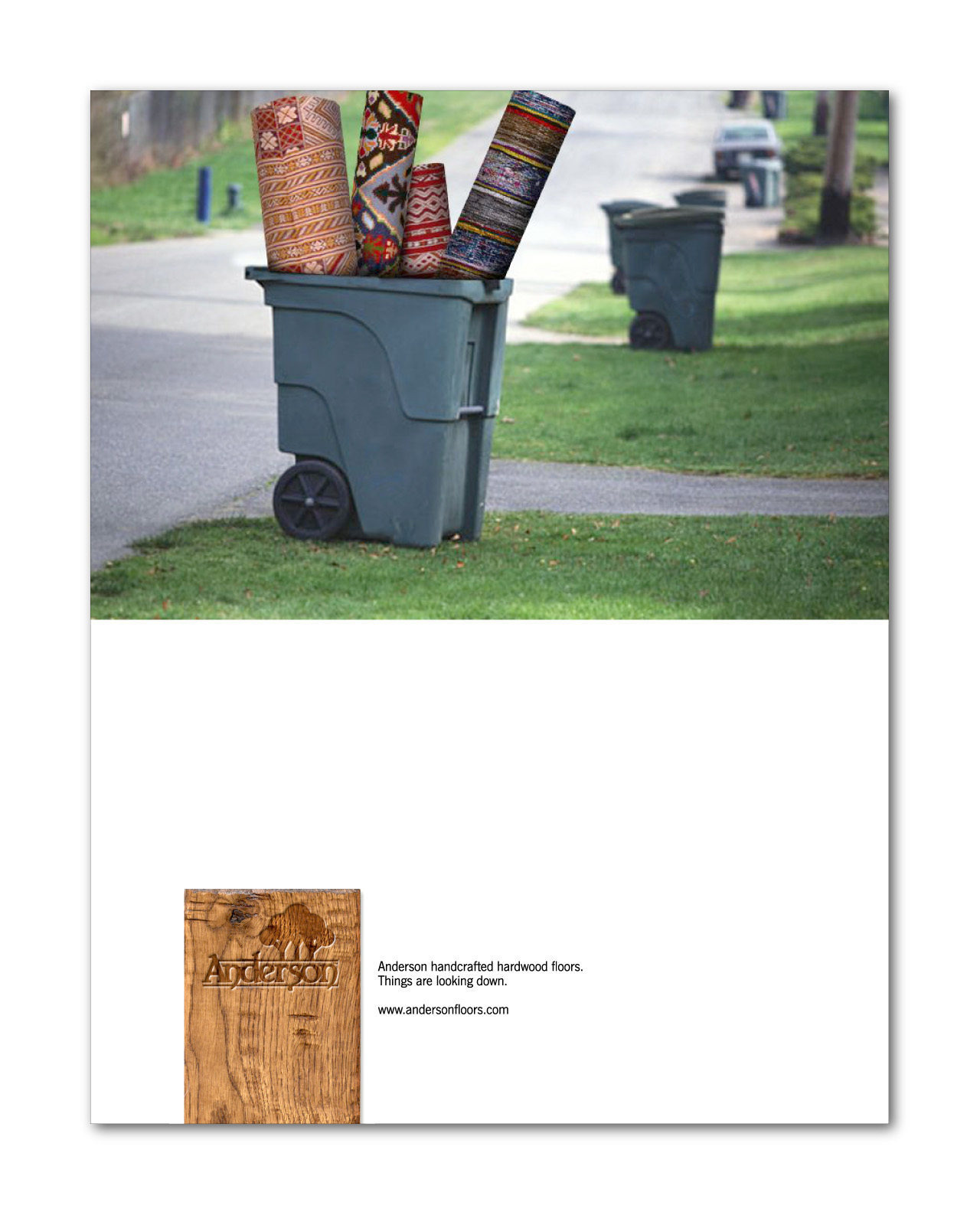

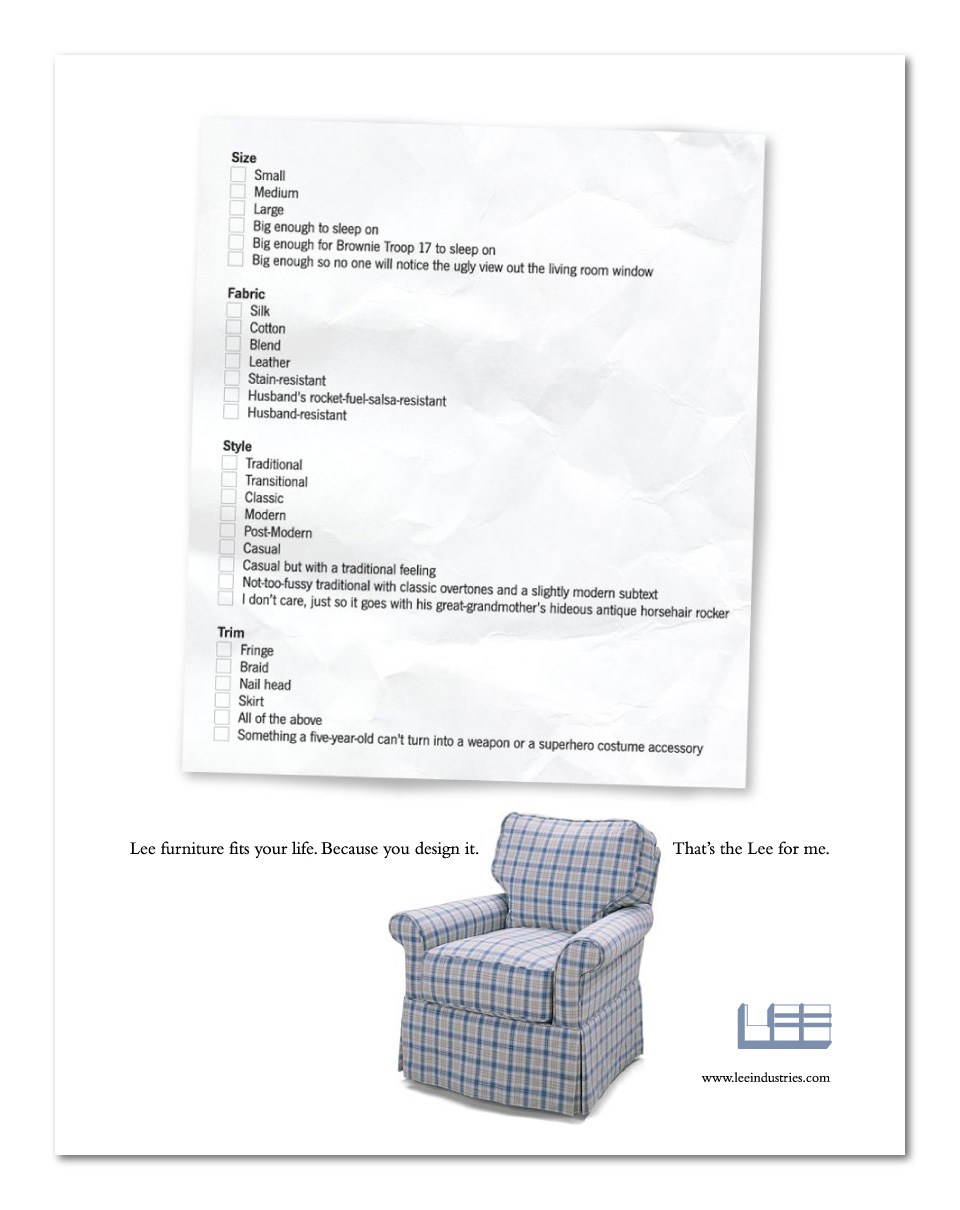

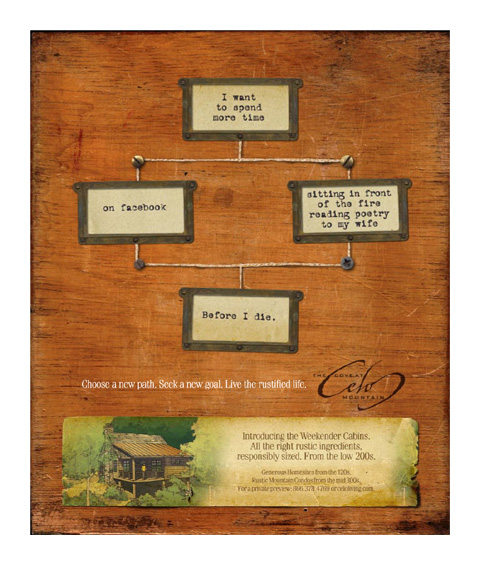

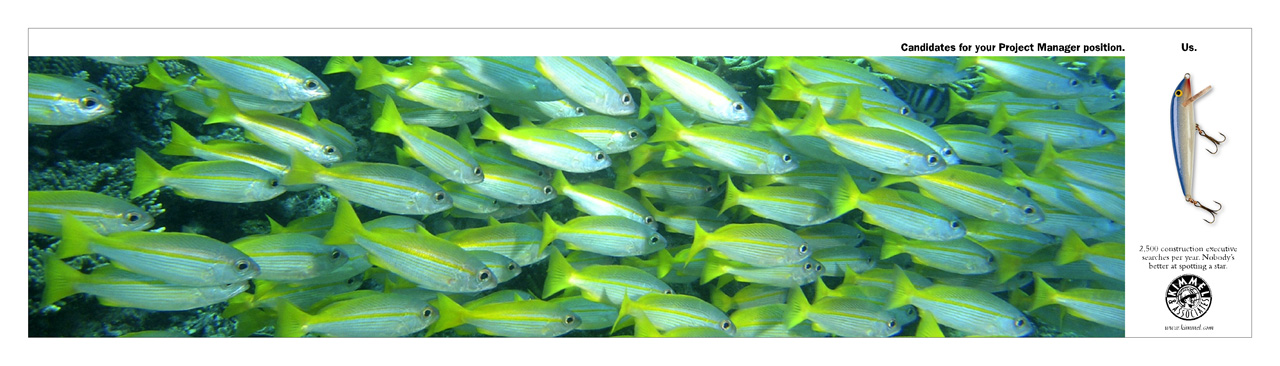

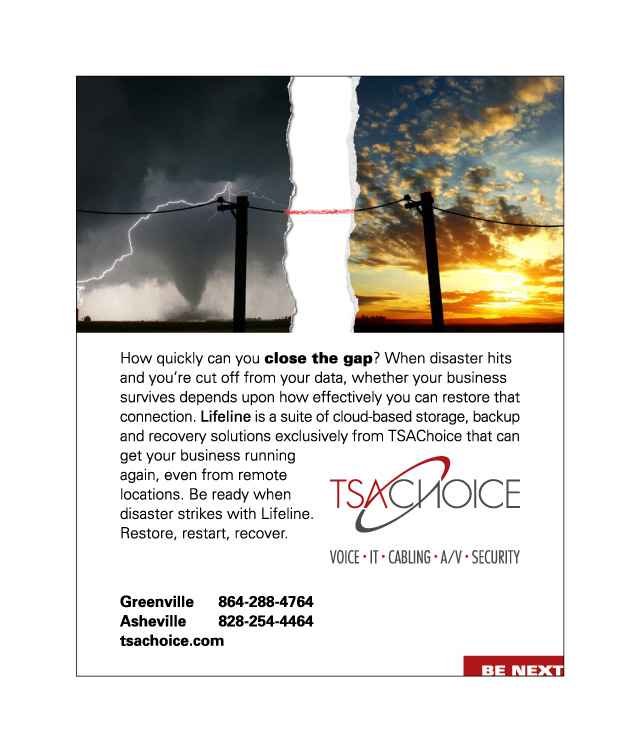

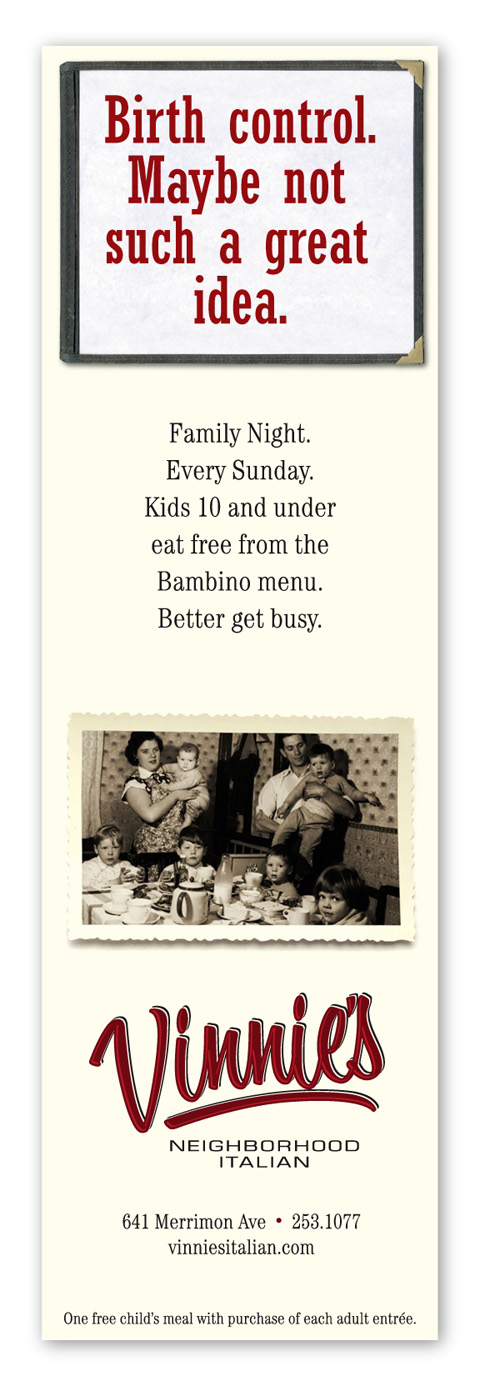

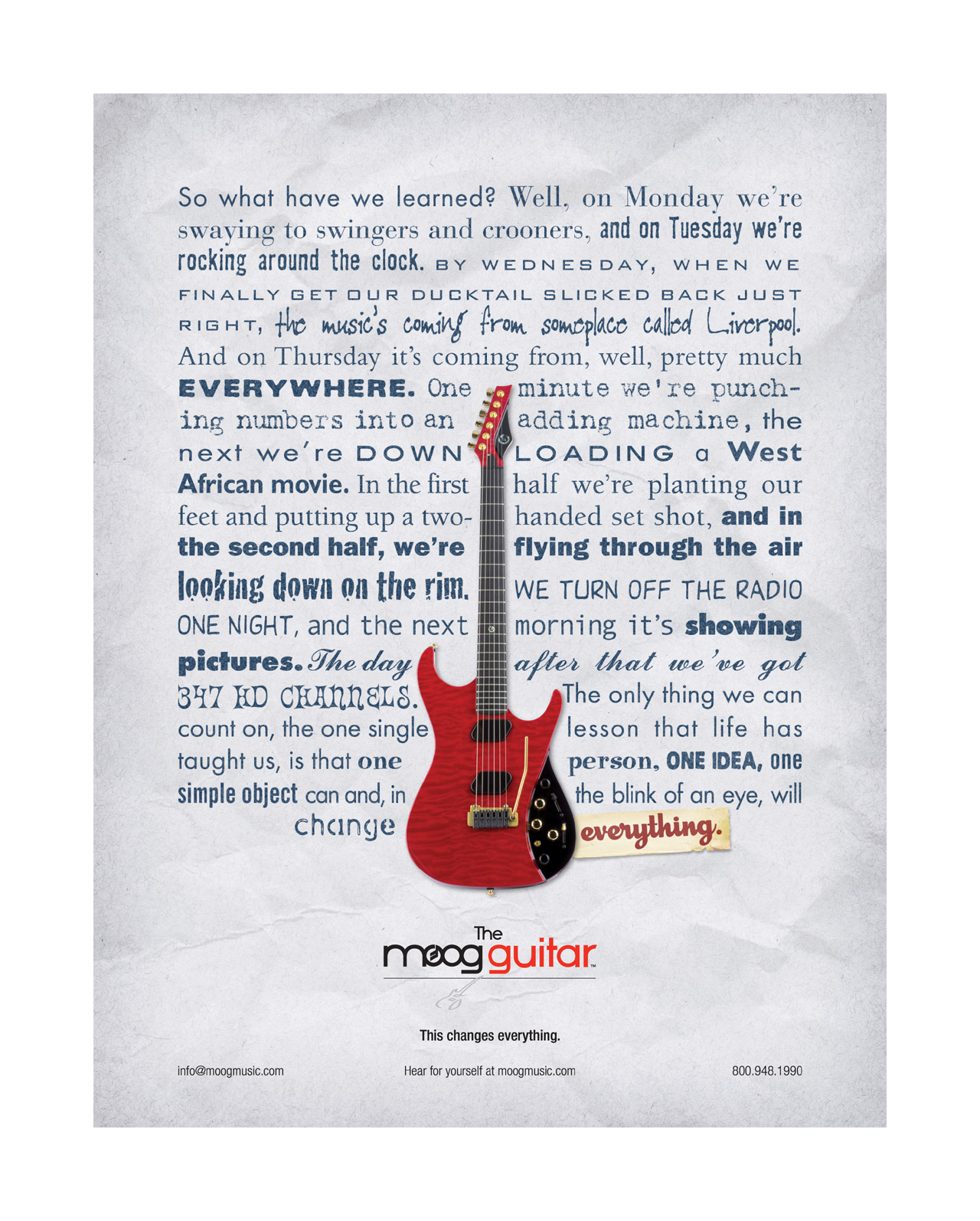

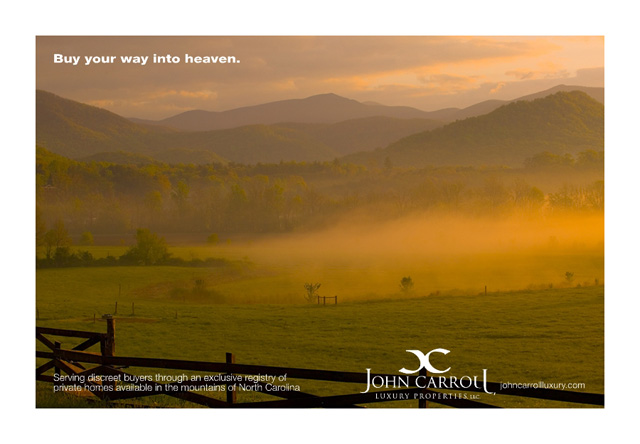

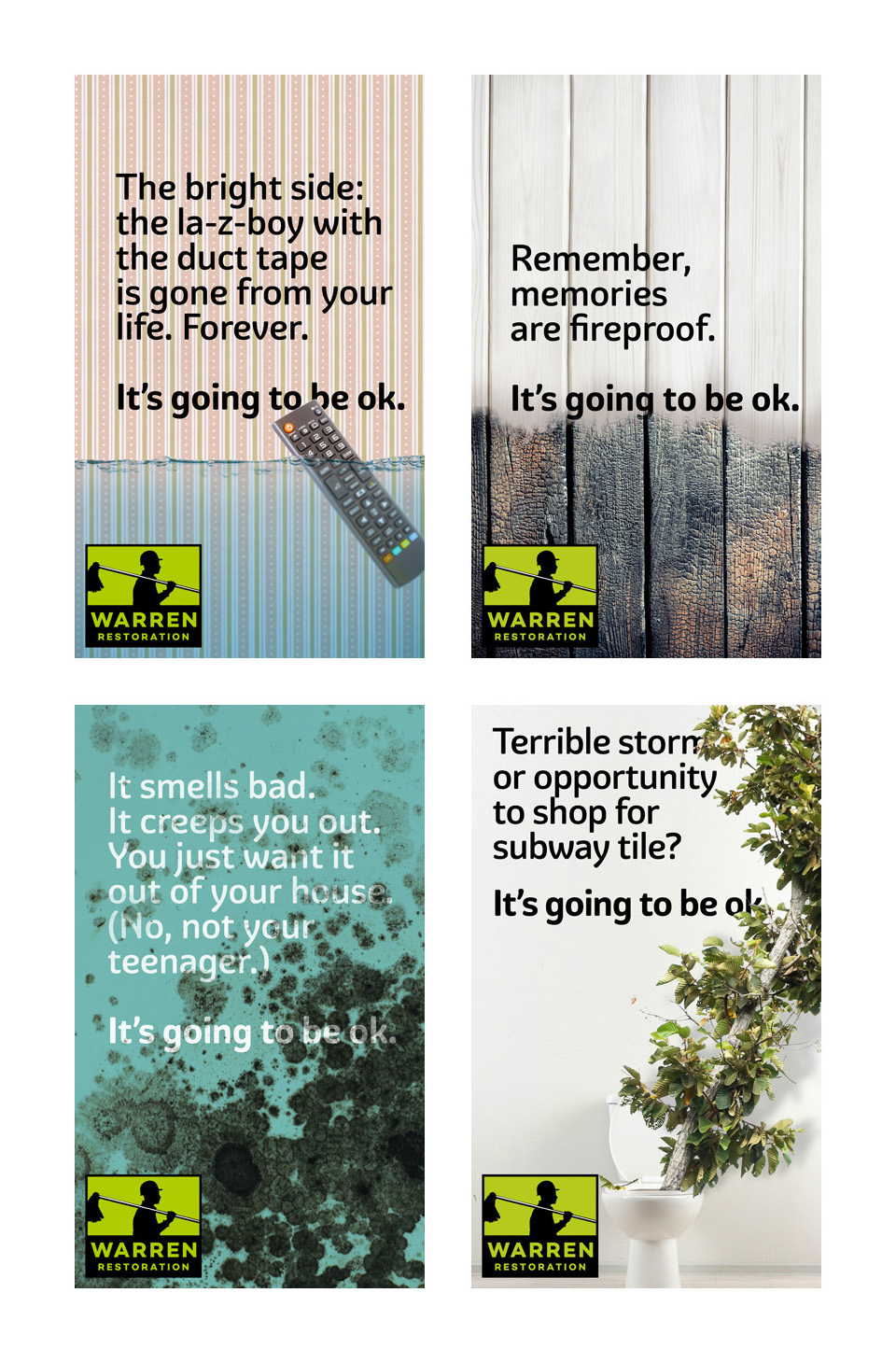

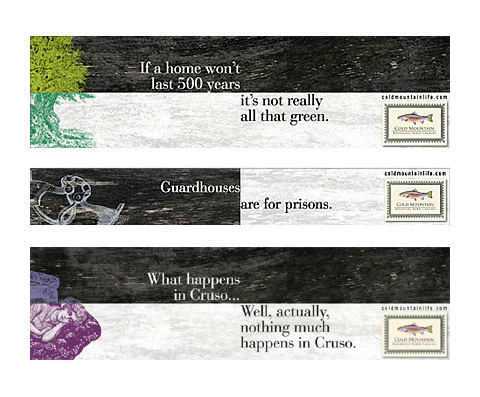

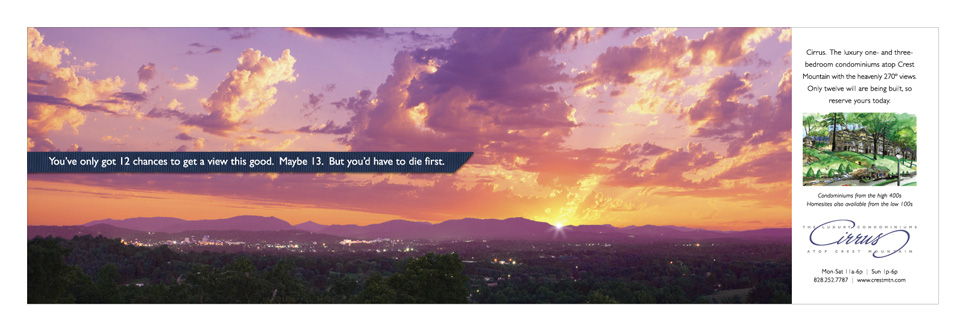

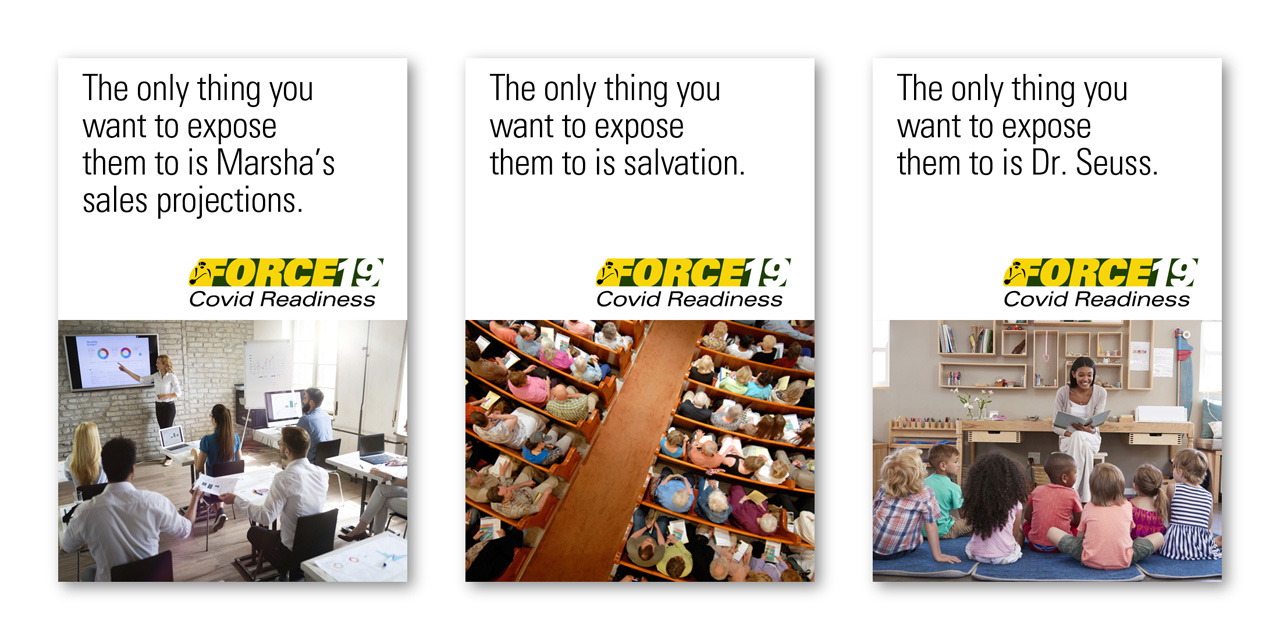

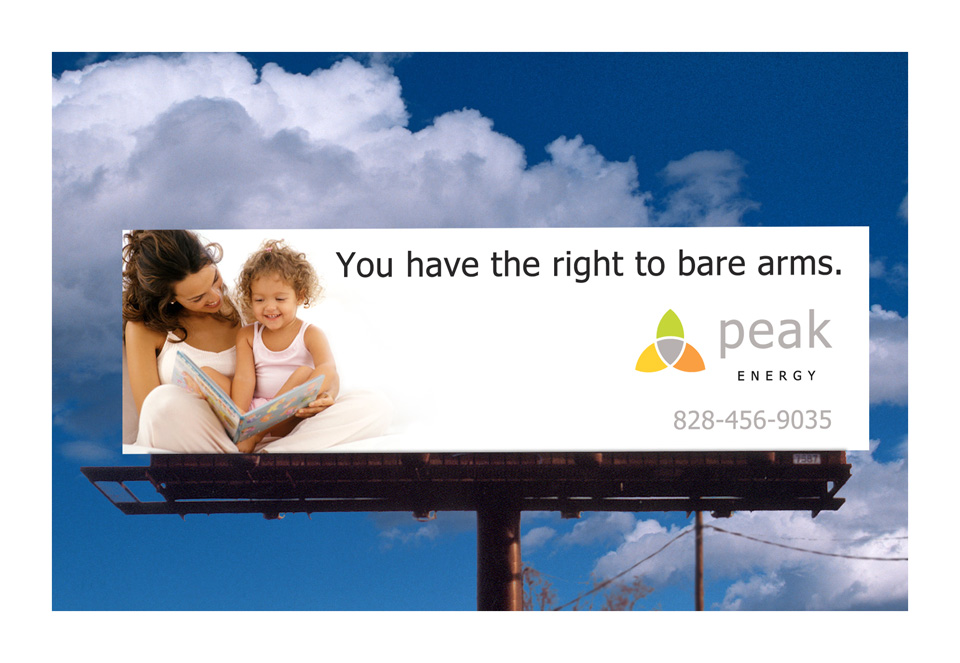

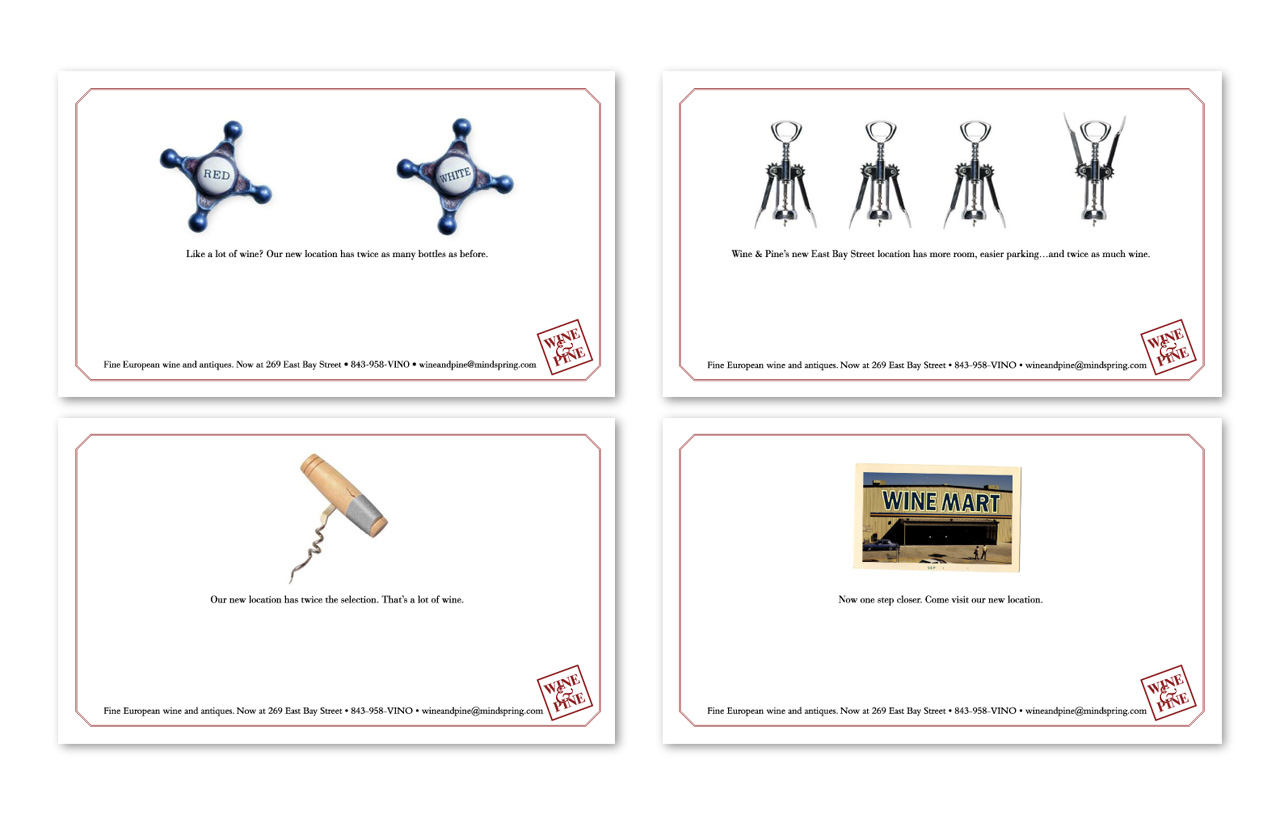

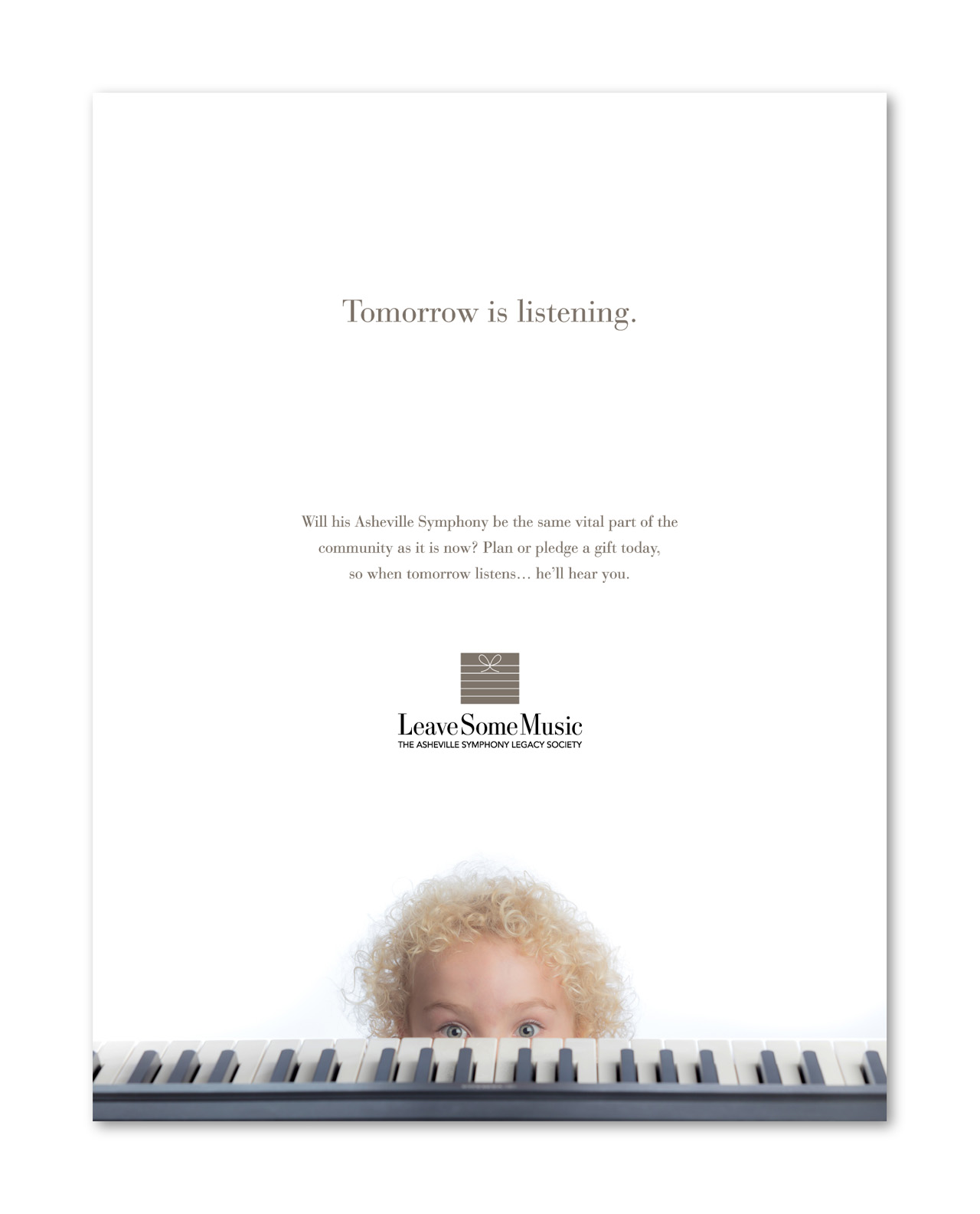

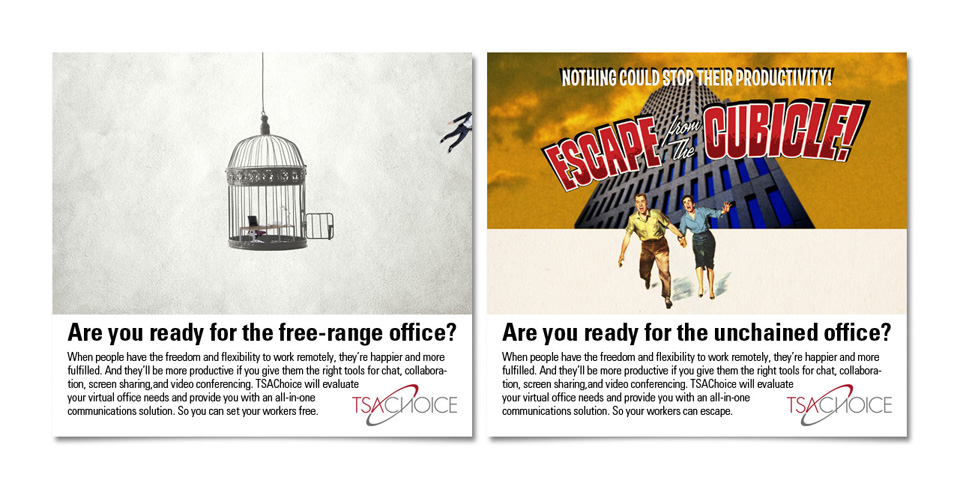

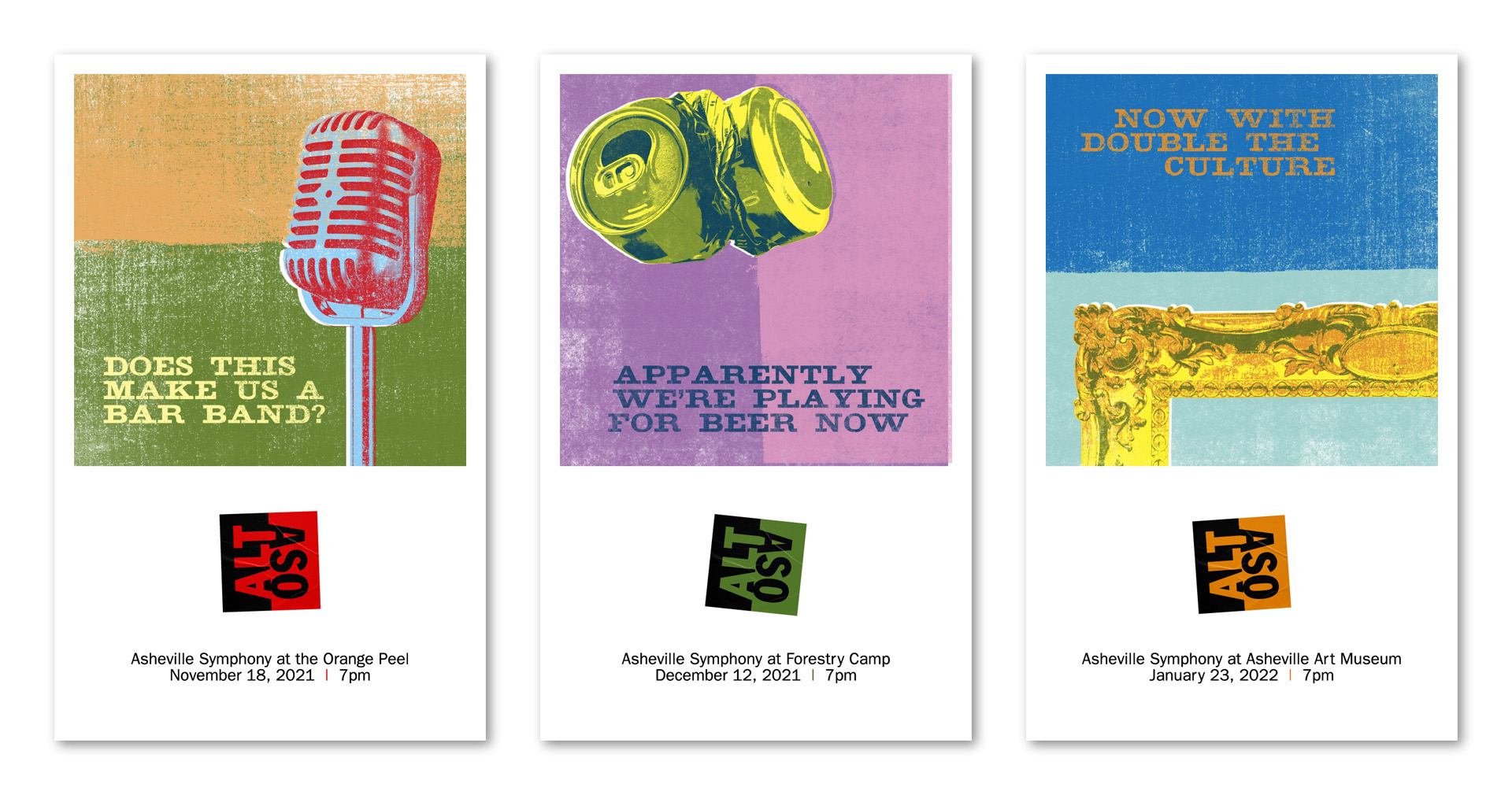

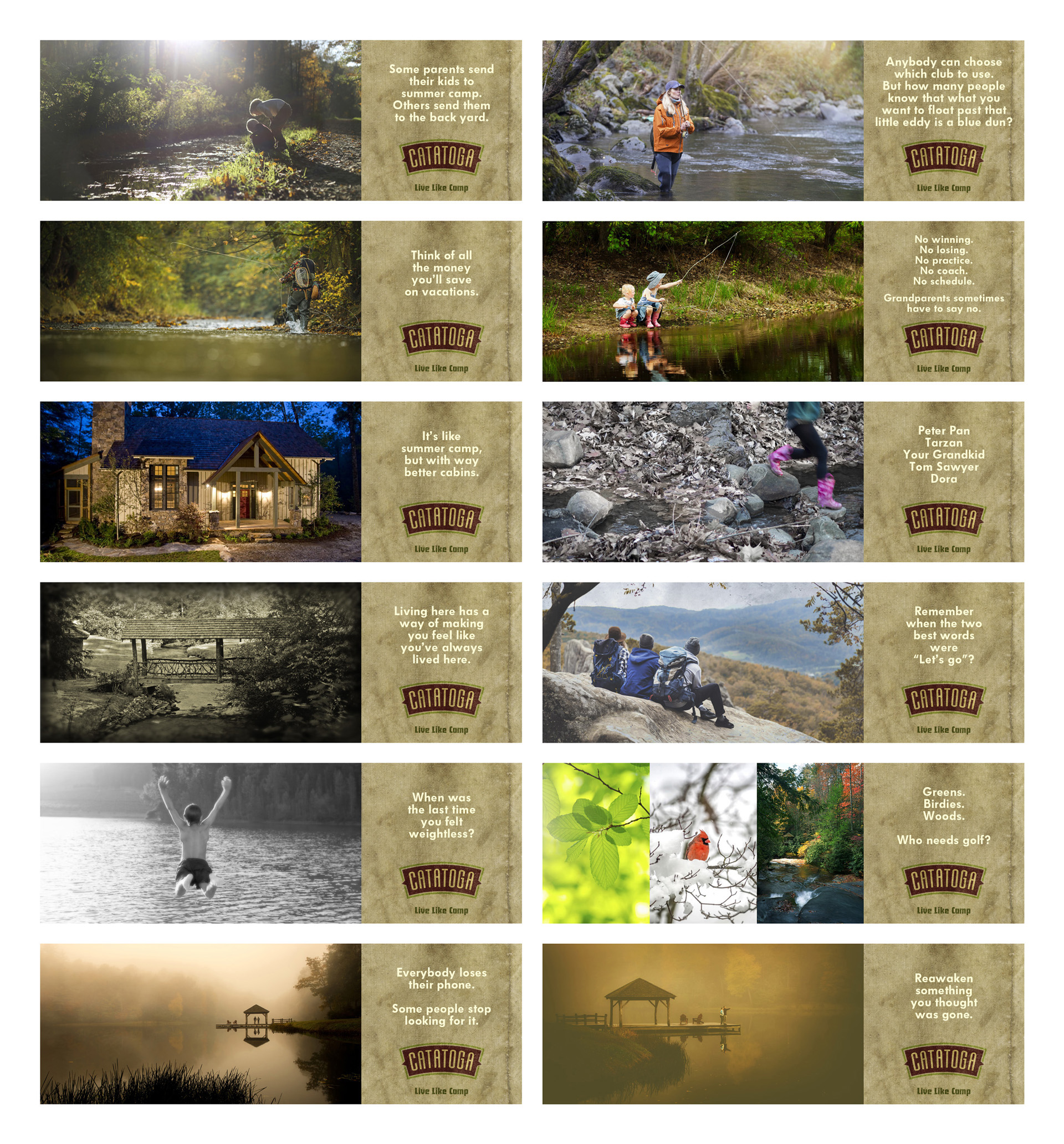

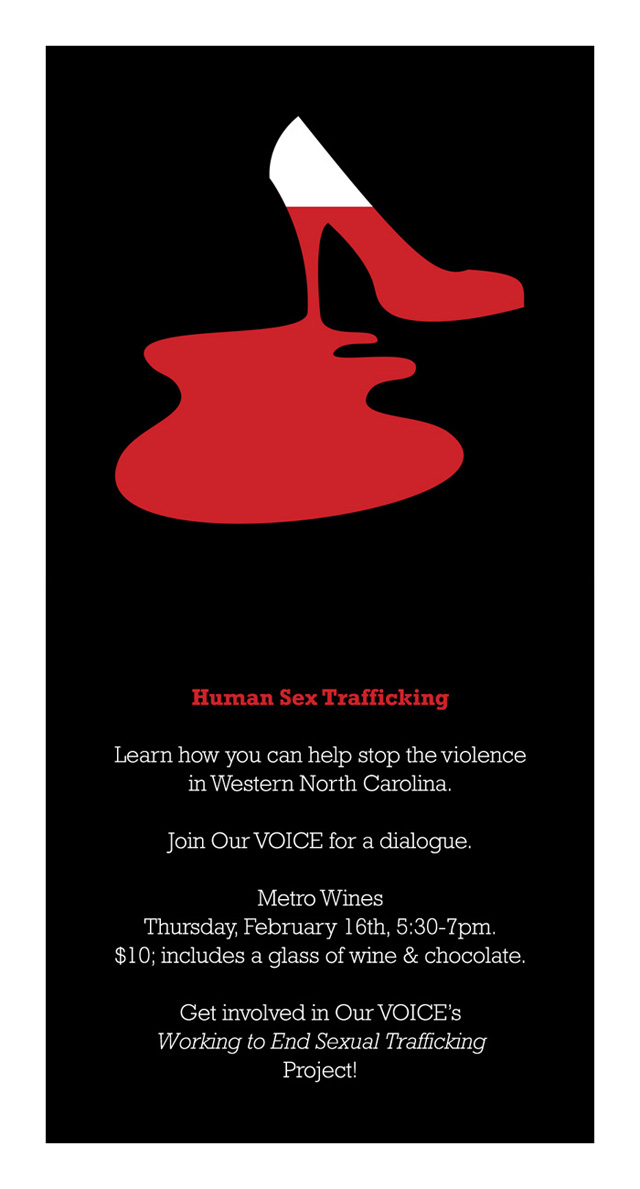

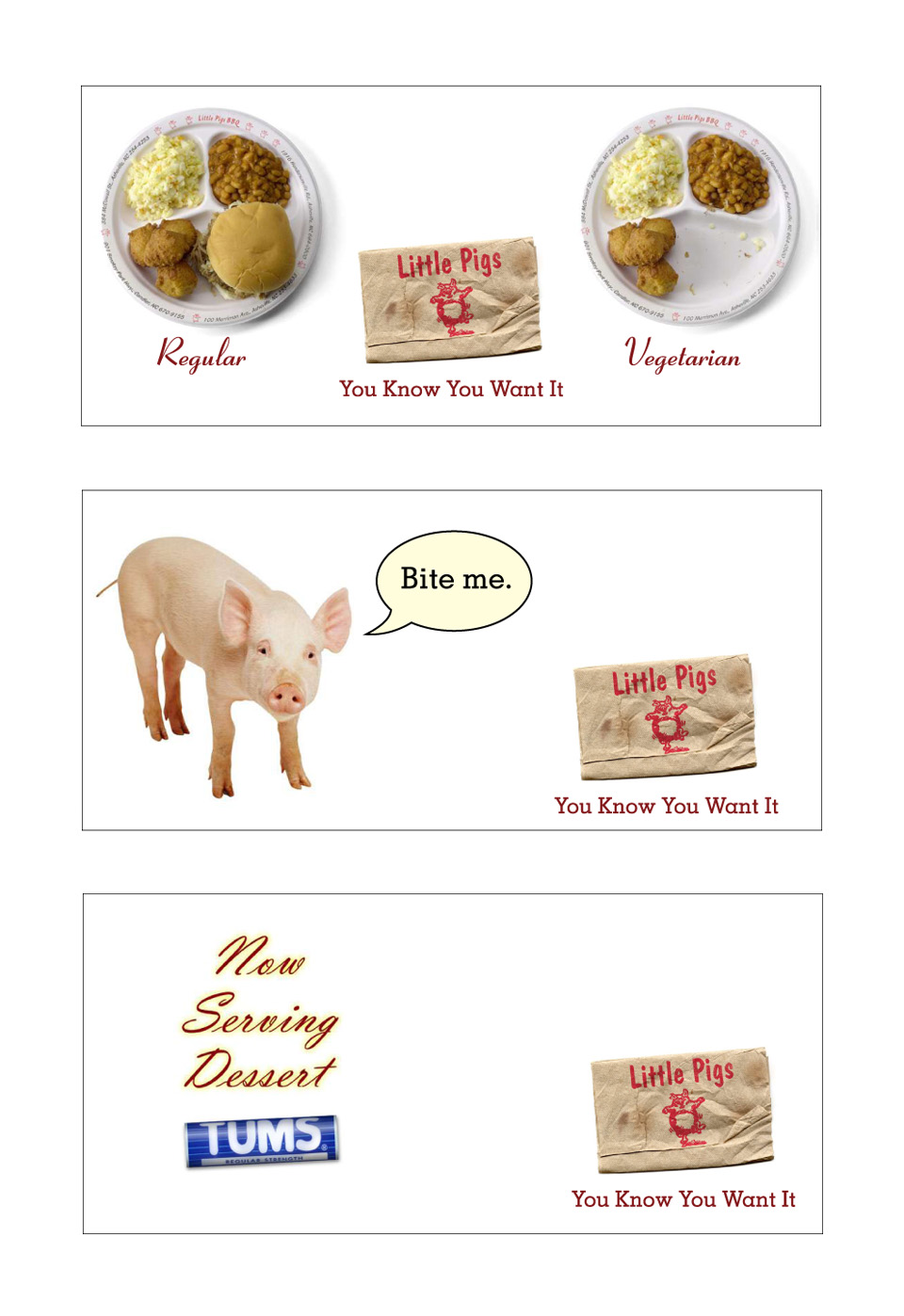

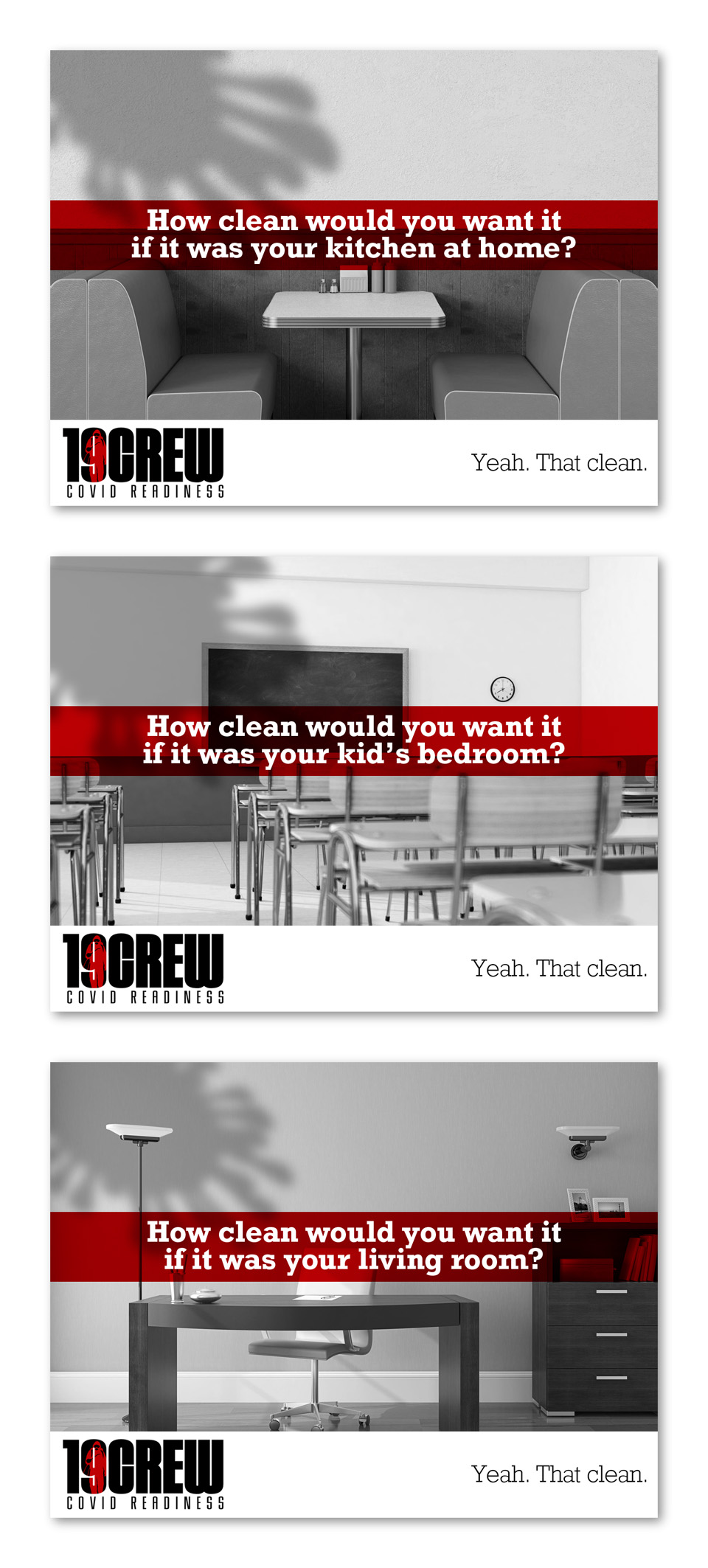

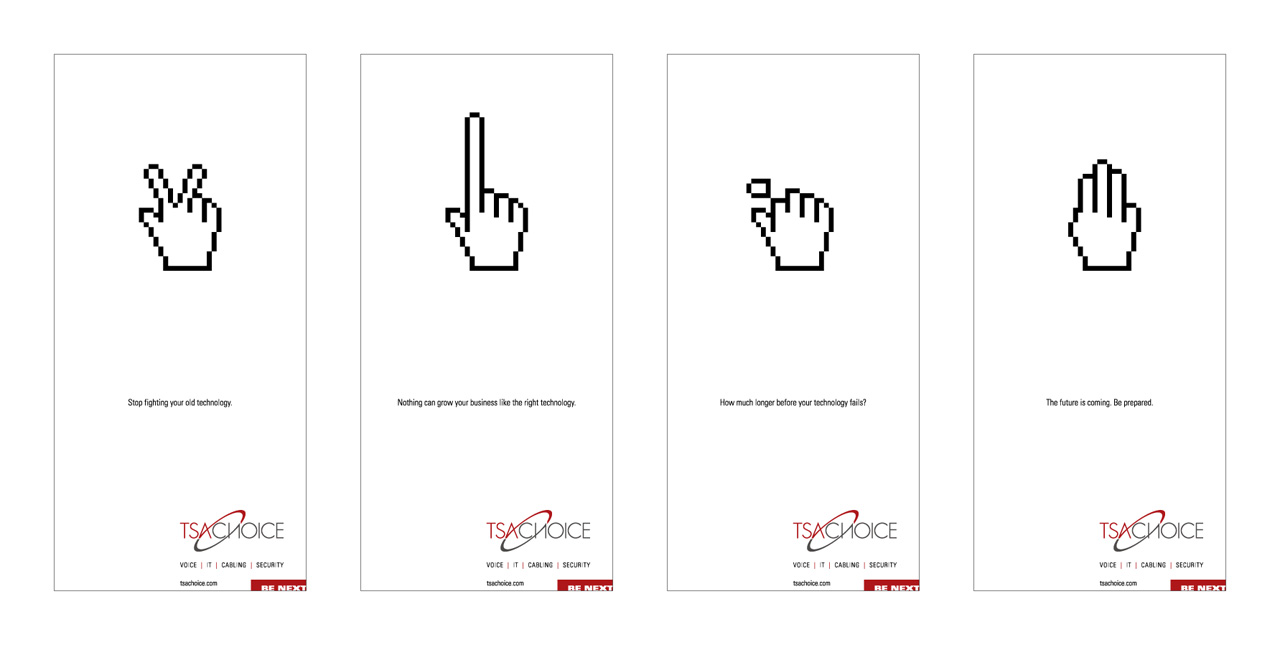

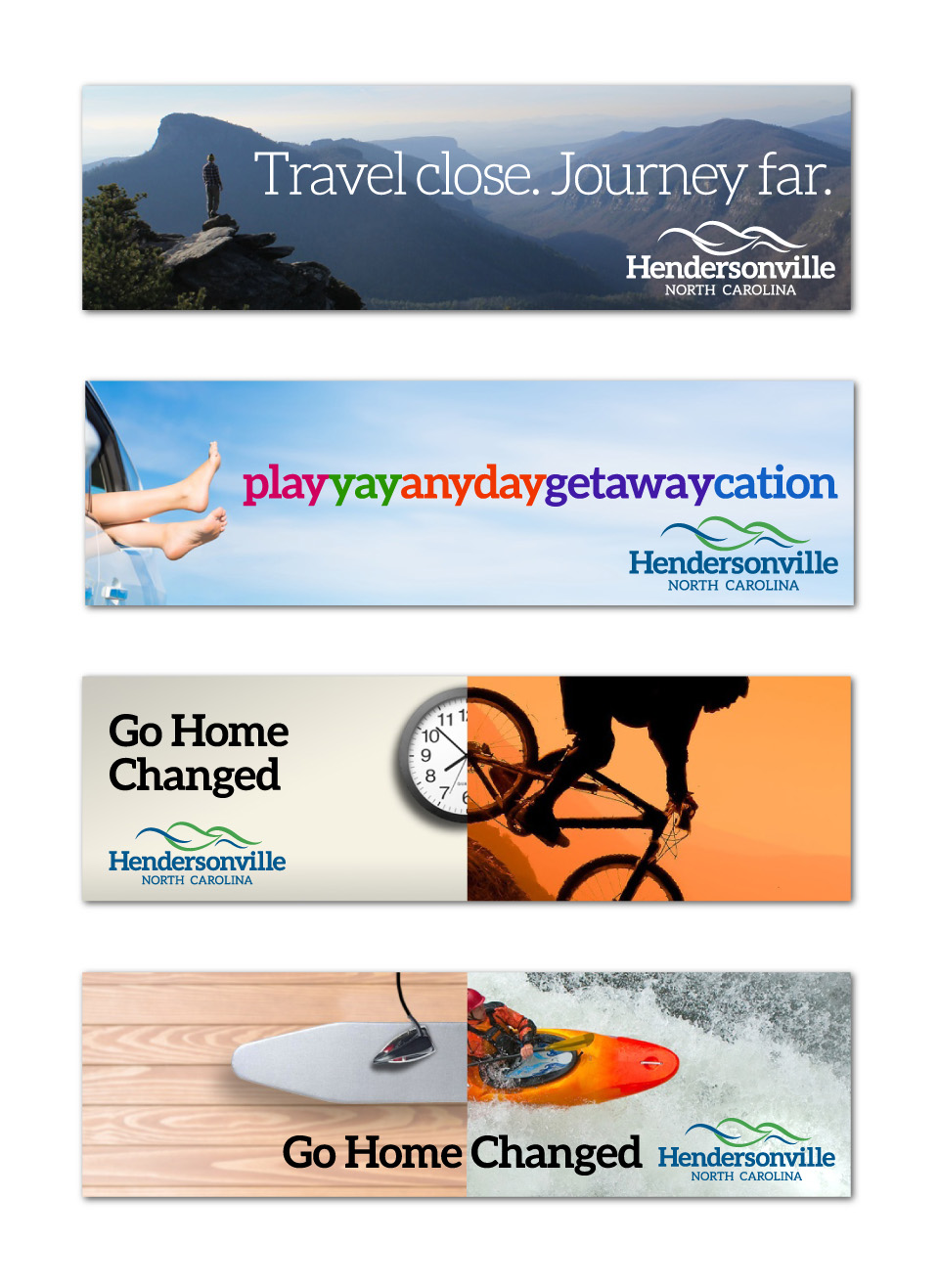

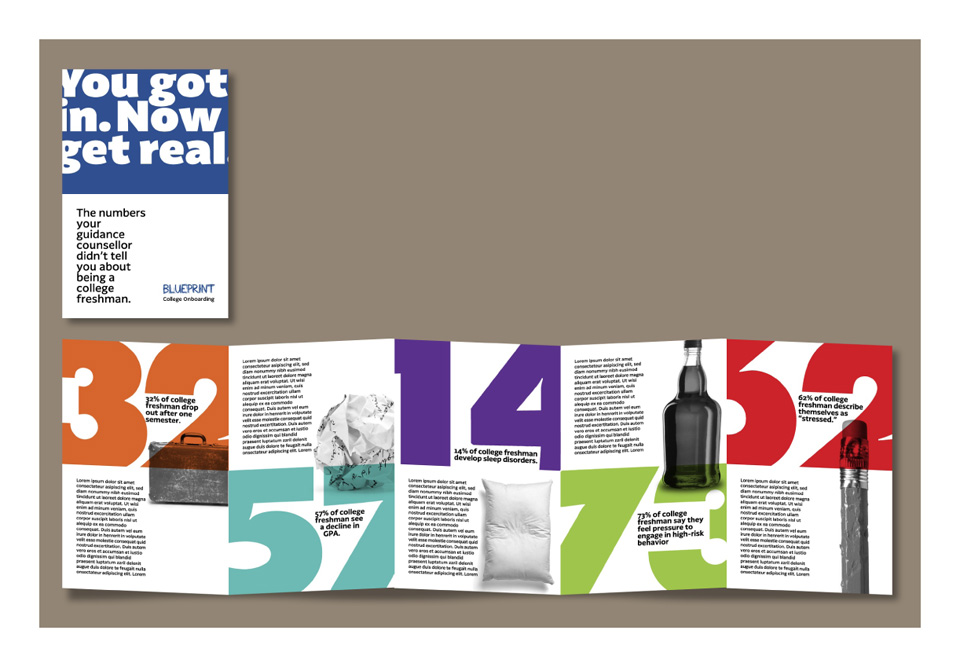

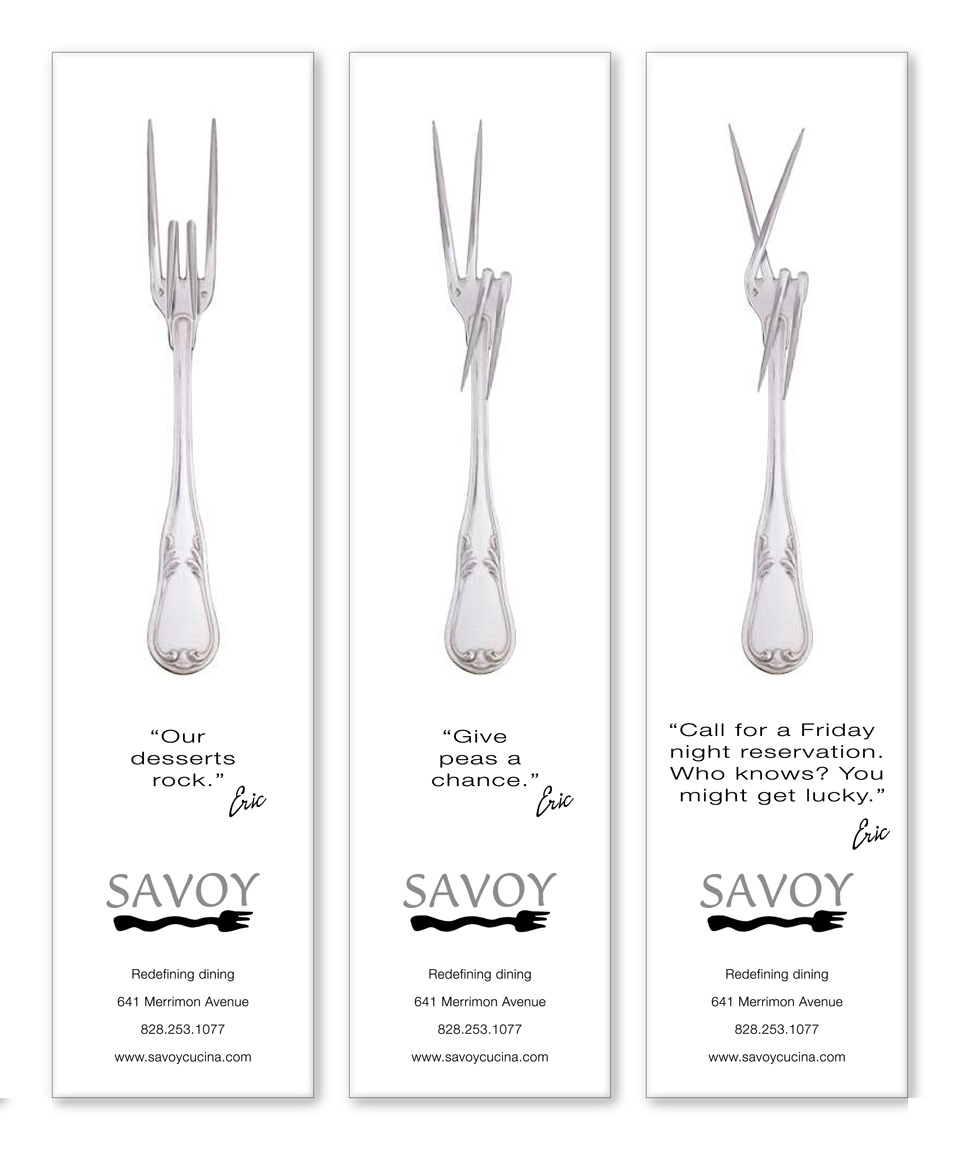

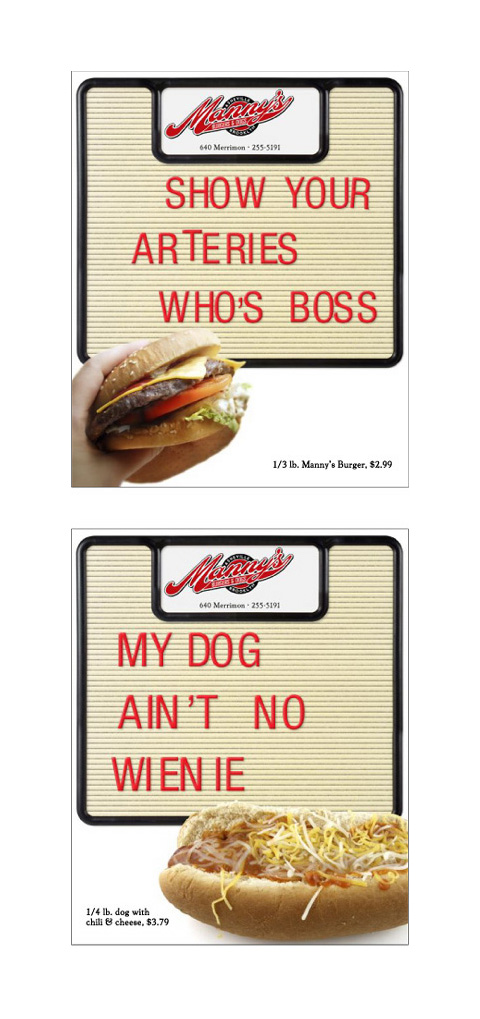

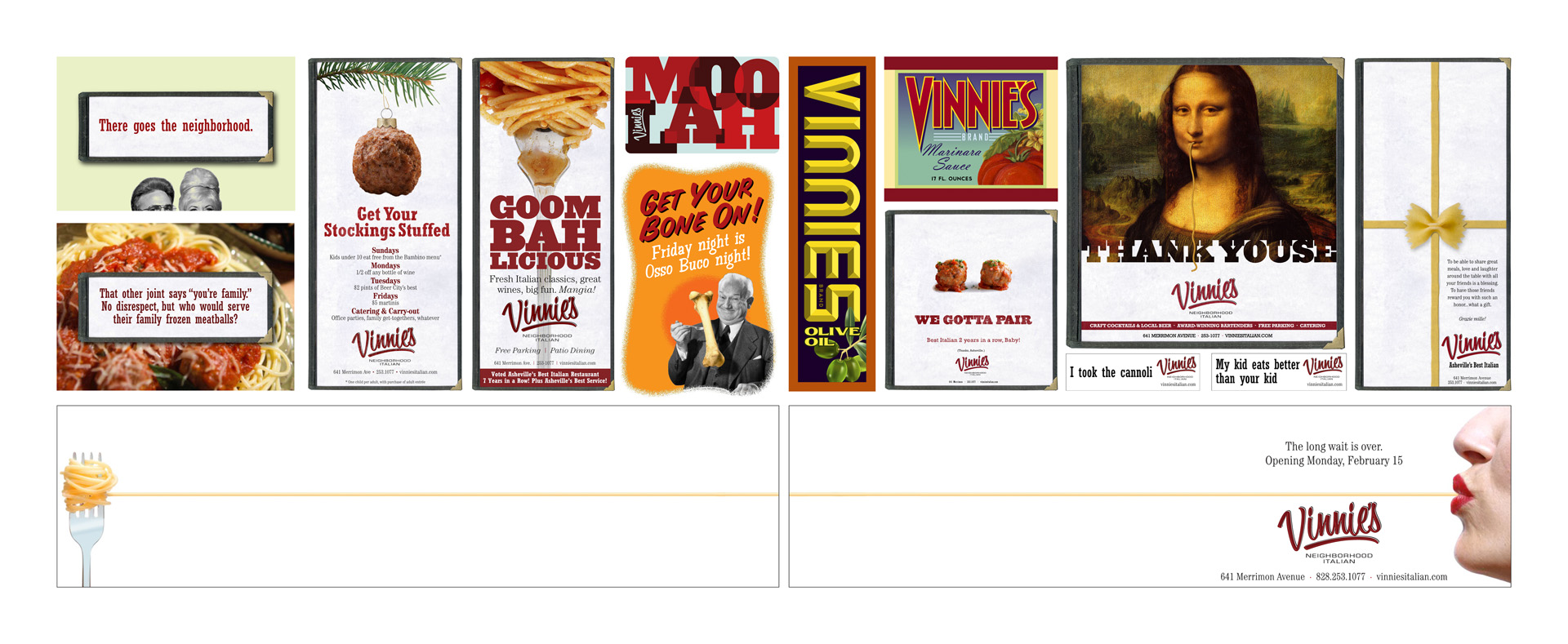

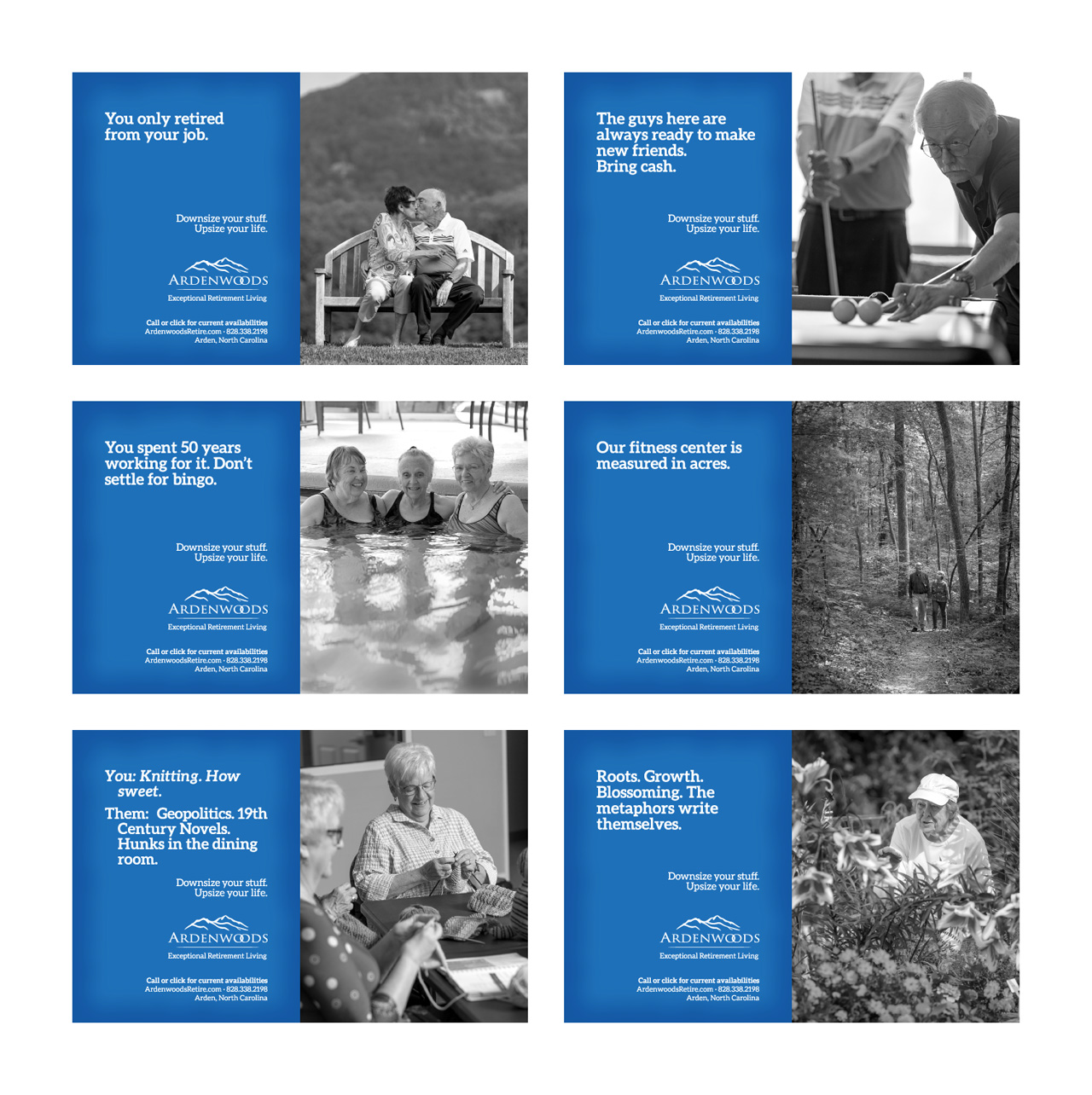

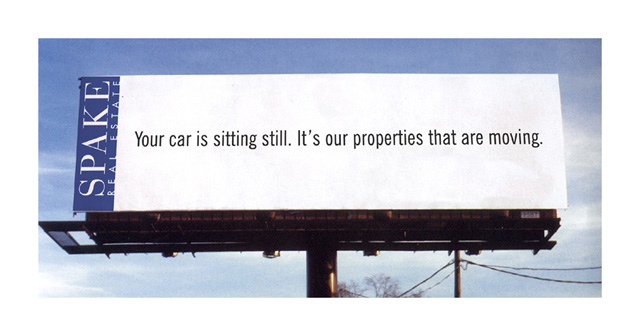

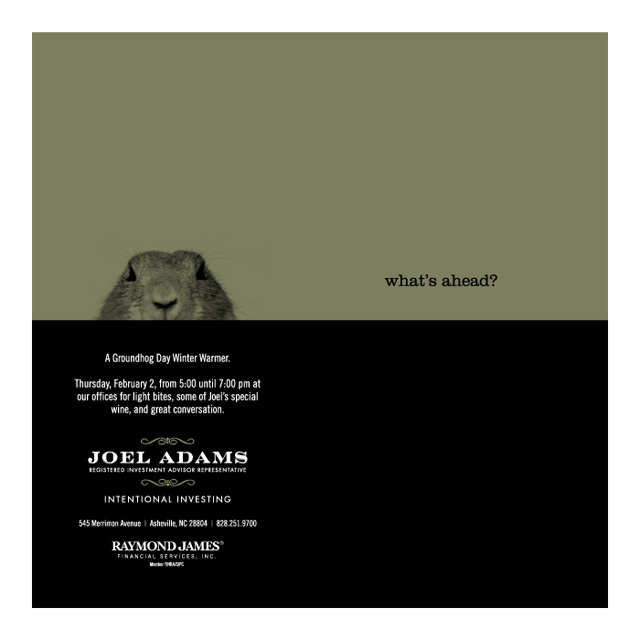

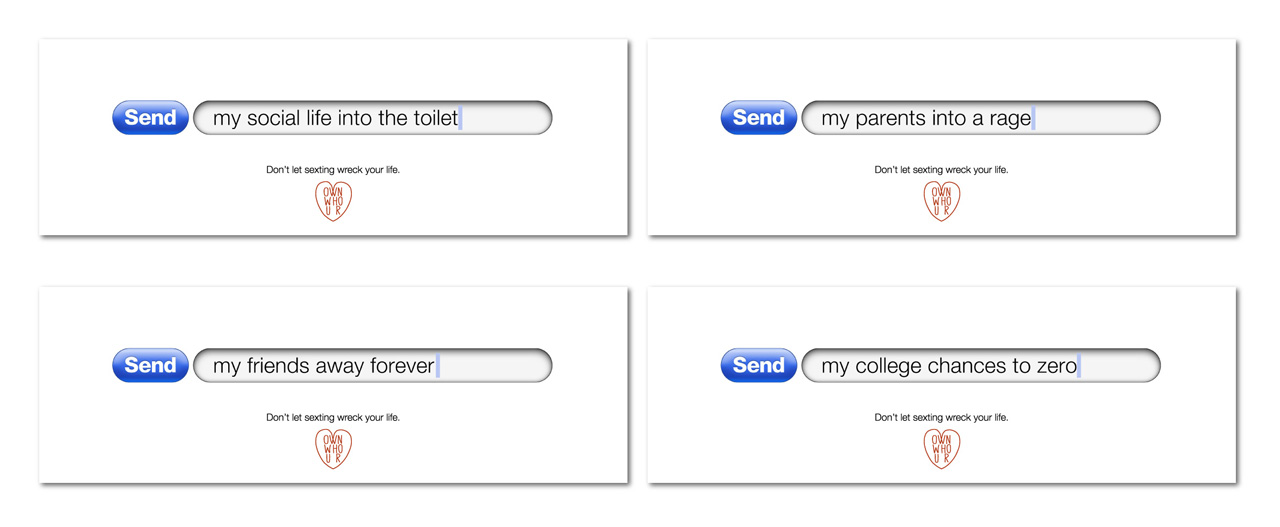

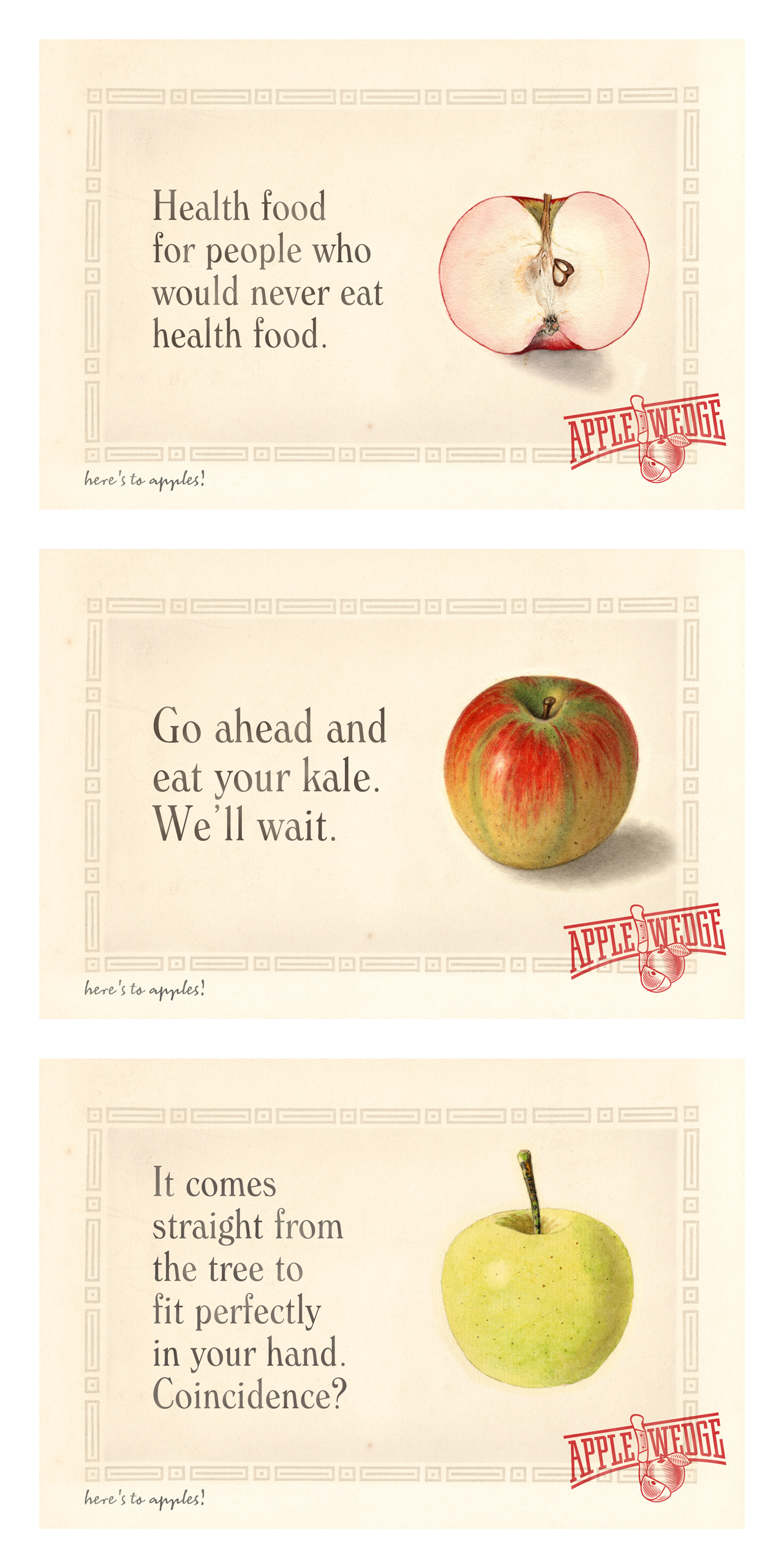

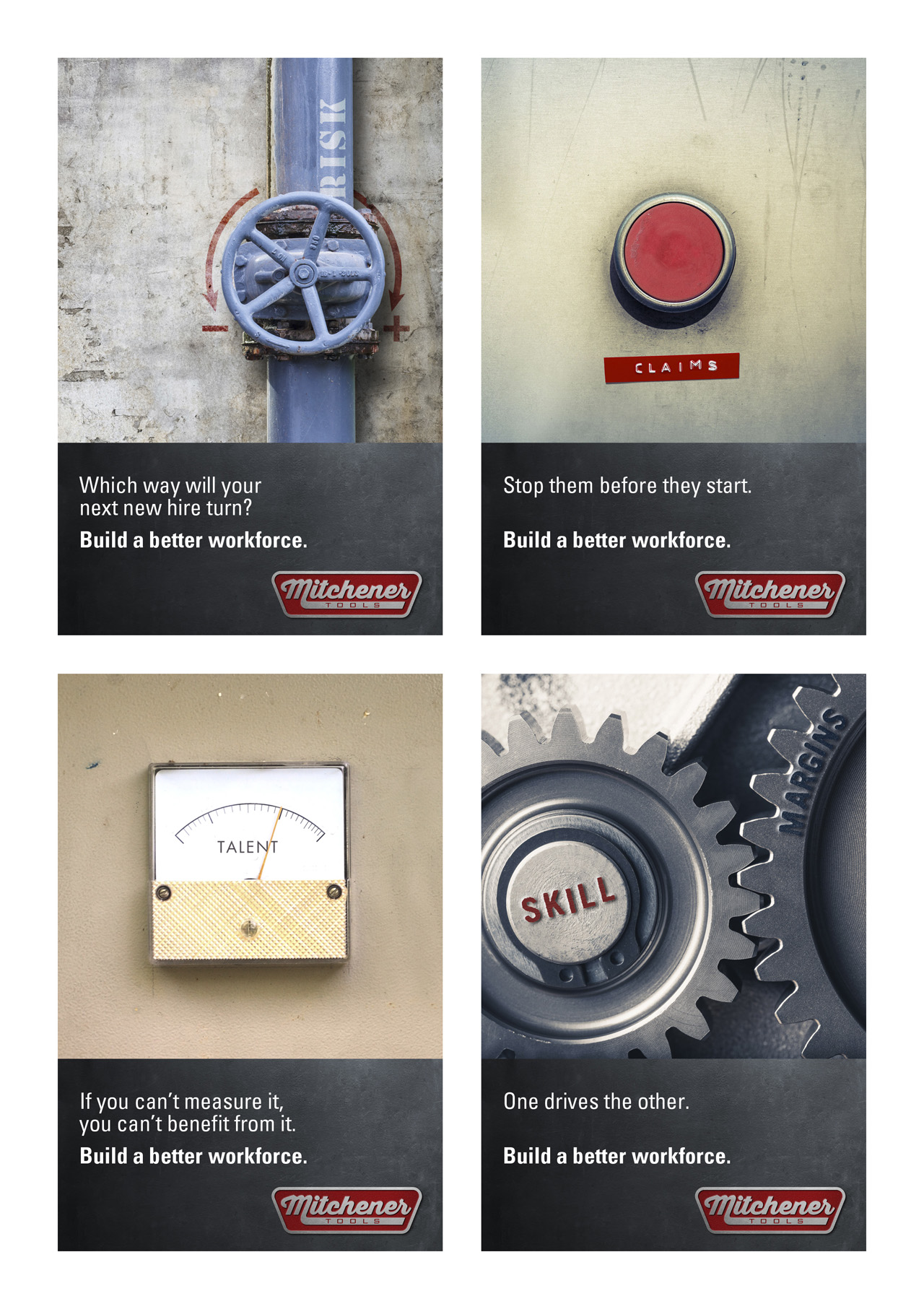

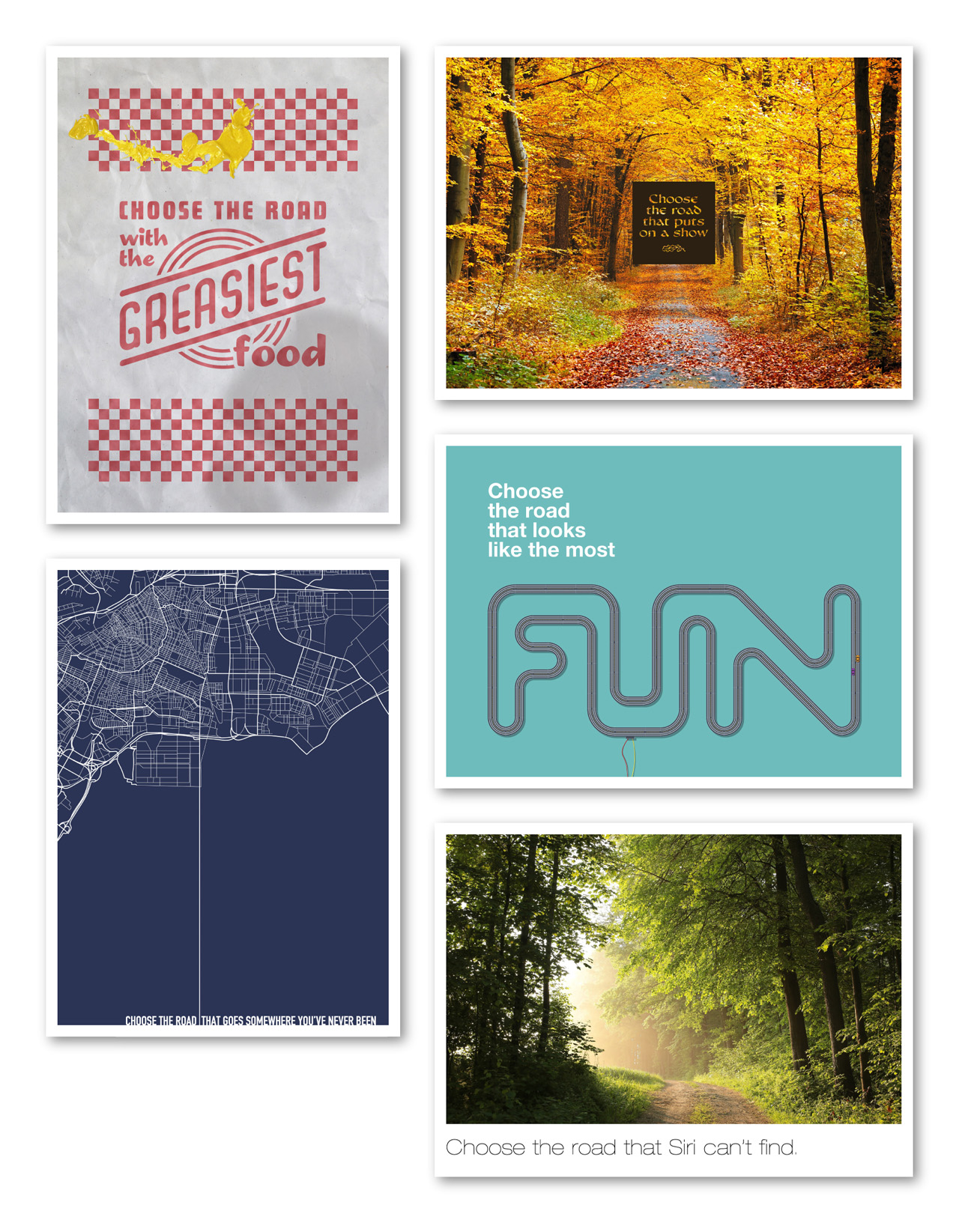

It’s exactly the same with your advertising. Once you identify the people you want to talk to, once you budget the piles of money it will take to get your message in front of them, don’t toss all of that effort away by saying something timid and lame. Quit worrying about offending, confusing, or shocking some tiny subset of your audience, because here’s the truth: somebody somewhere will be offended, confused or shocked no matter what you say. So just go ahead and say it. Be bold, loud, outeageous, silly, weird, confrontational, heretical, startling, and challenging. Because the alternative is to be invisible. Not exactly the point.

Nobody except your mom wants to see your ad. You have to change their minds.

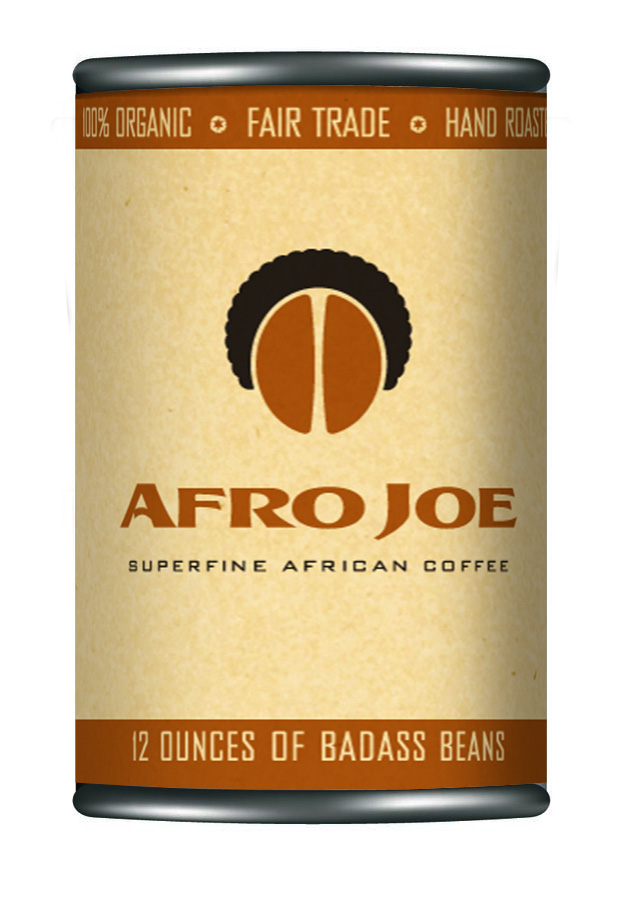

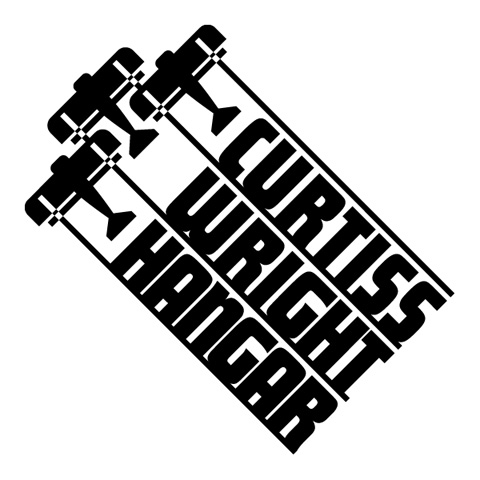

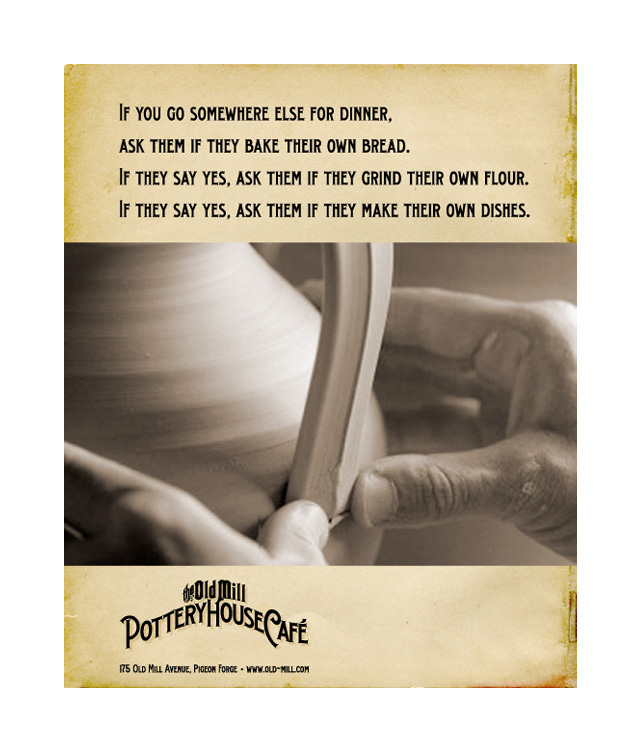

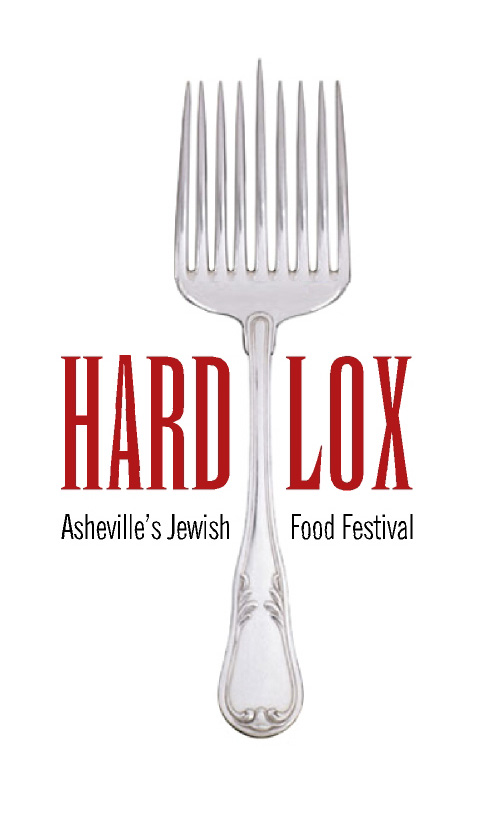

Here’s the thing about logos. They don’t have to be a graphic depiction of your business. That’s right. Let’s say you run a logistics company. That doesn’t mean your logo has to include planes, trucks, or trains. Your law office doesn’t have to show a scale, your investment firm money. or your jewelry store a diamond. Sure, if it’s easy to work a hammer into your contractor logo, go right ahead. Just remember: McDonalds’ logo doesn’t show a hamburger, Nike’s doesn’t show a running shoe, Chevrolets’s isn’t a car, and Apple’s is not a picture of a computer. All a good logo has to be is sort of evocative of something (speed, integrity, fun, protection, whatever), sticky enough to lodge somewhere in the memory, and consistently used.

I hate to break it to you, but nobody cares that you run a family-owned business. Of all the considerations that go into my choice of what products I buy—quality, speed of delivery, price, carbon-neutrality—the fact that your nephews painted it and your Aunt Mildred loaded it onto the truck matters just about least. Remember: the mafia, Purdure Pharma and Trump Holdings are all family-owned.

At this point I feel like I’m in a contest with my chosen career to see which of us dies first. But as a twenty-something, I timed it perfectly. I got to learn my craft when it was ascendant, and practice it when it was at its culture-defining peak. Not that I’m claiming to have done any of the defining; it was just nice to know that I was participating, in a small-market sort of way, in the Advertising Business. I couldn’t get enough of it. I, a fine-art major wholly ignorant of American commerce, voraciously learned design and art direction and copywriting and print production and audio and video production and media strategy and brand management just to be immersed in the coolness of it all.

Now that time is trying to steer me toward the pasture, my beloved ad biz is right behind. The 30-second spot and the full-page magazine ad and the 36-page viewbook are quaint curios, like dial telephones and V8 motors.

AI now designs logos and writes copy and “shoots” “photographs.”

To be sure, there is still a massive advertising-industrial complex churning out the sell. But what’s vanishing is the sense that we’re doing something artful and conversation-worthy.

I’m not trying to be all weepy here, understand. I know that most advertising is and always was crap, that capitalism morphs and contorts to suit its insatiable cravings, that old people should graciously cede their relevence to the young, and that new ideas are almost always better than old ones. So not complaining. I’m just saying I got really lucky with my timing.

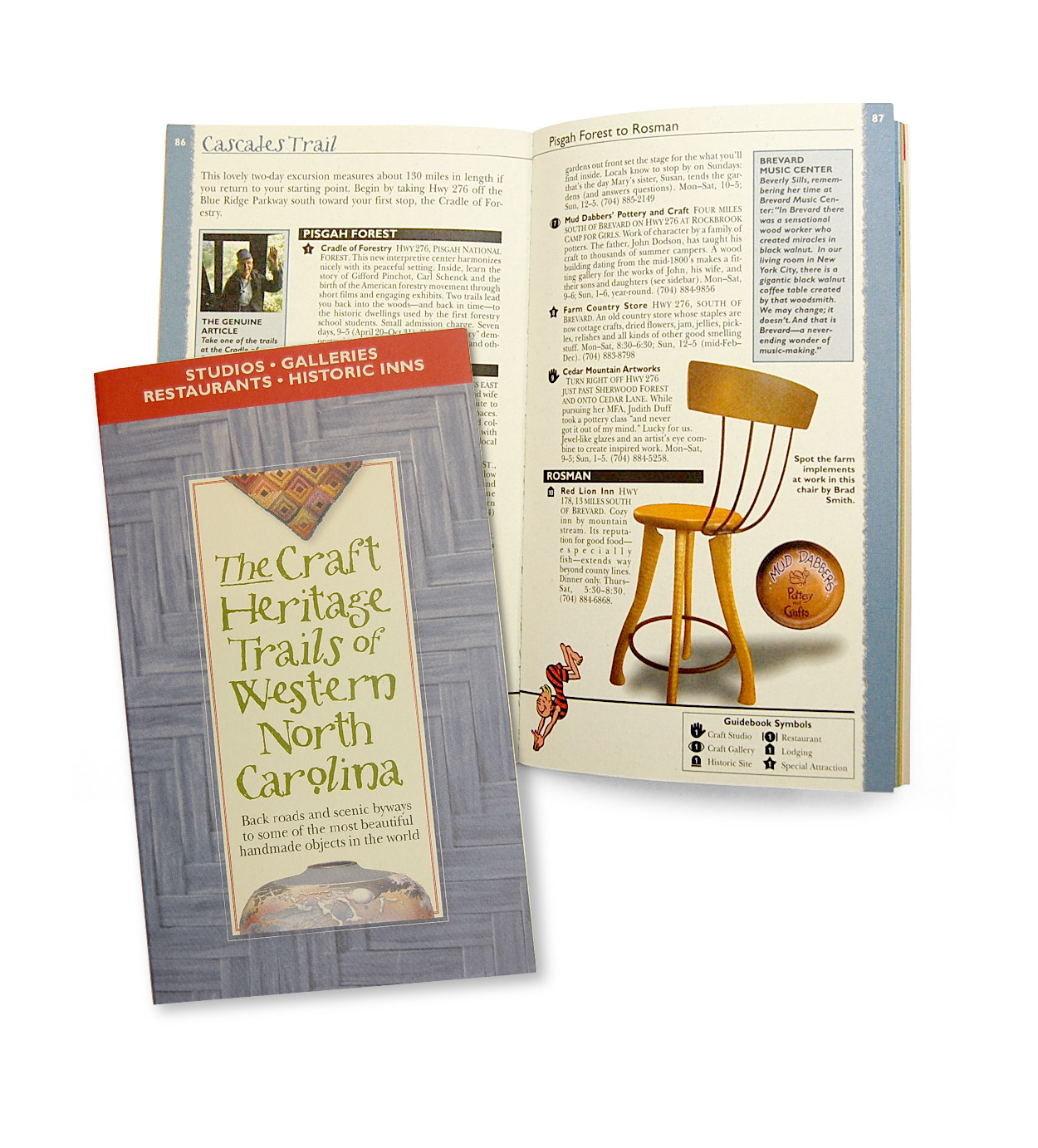

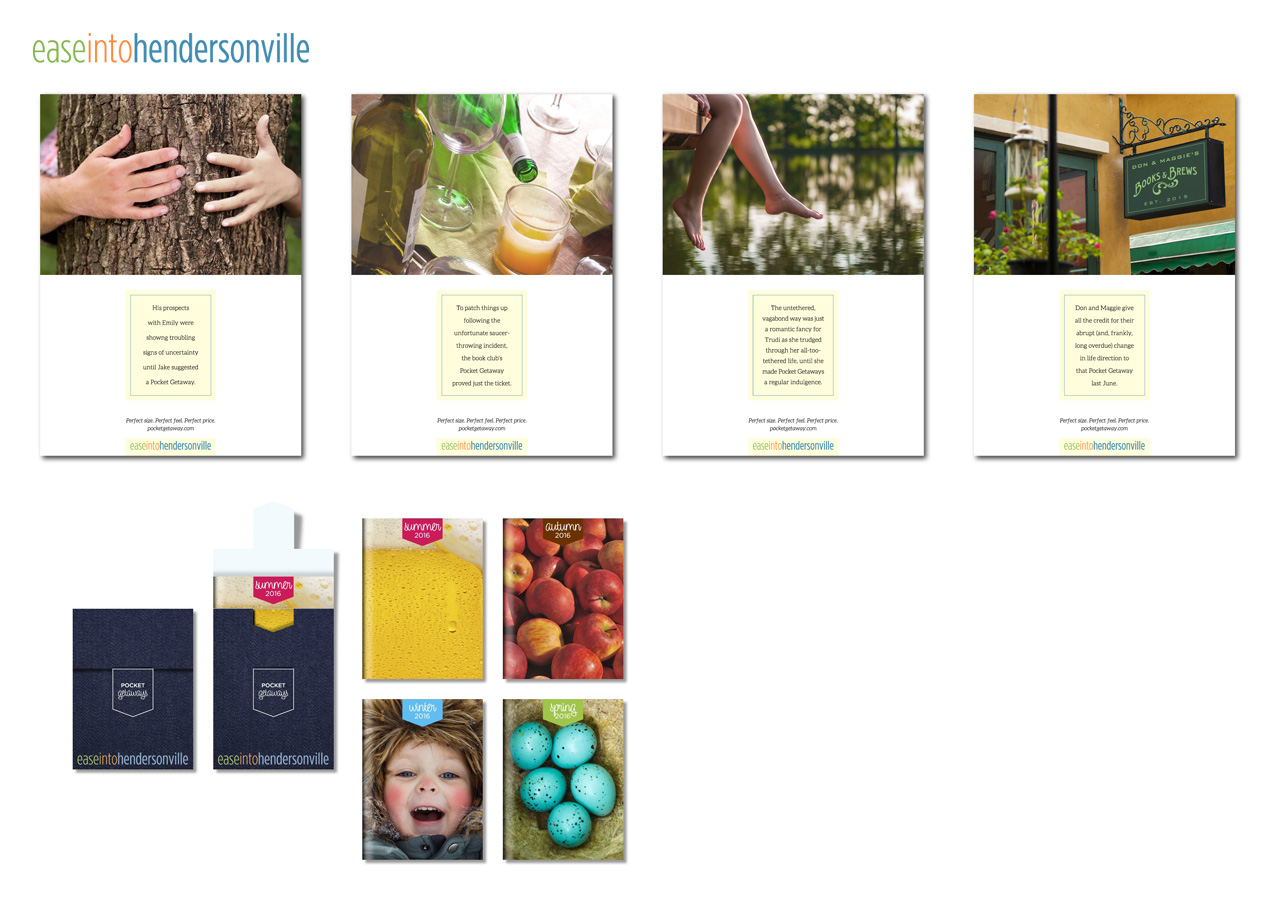

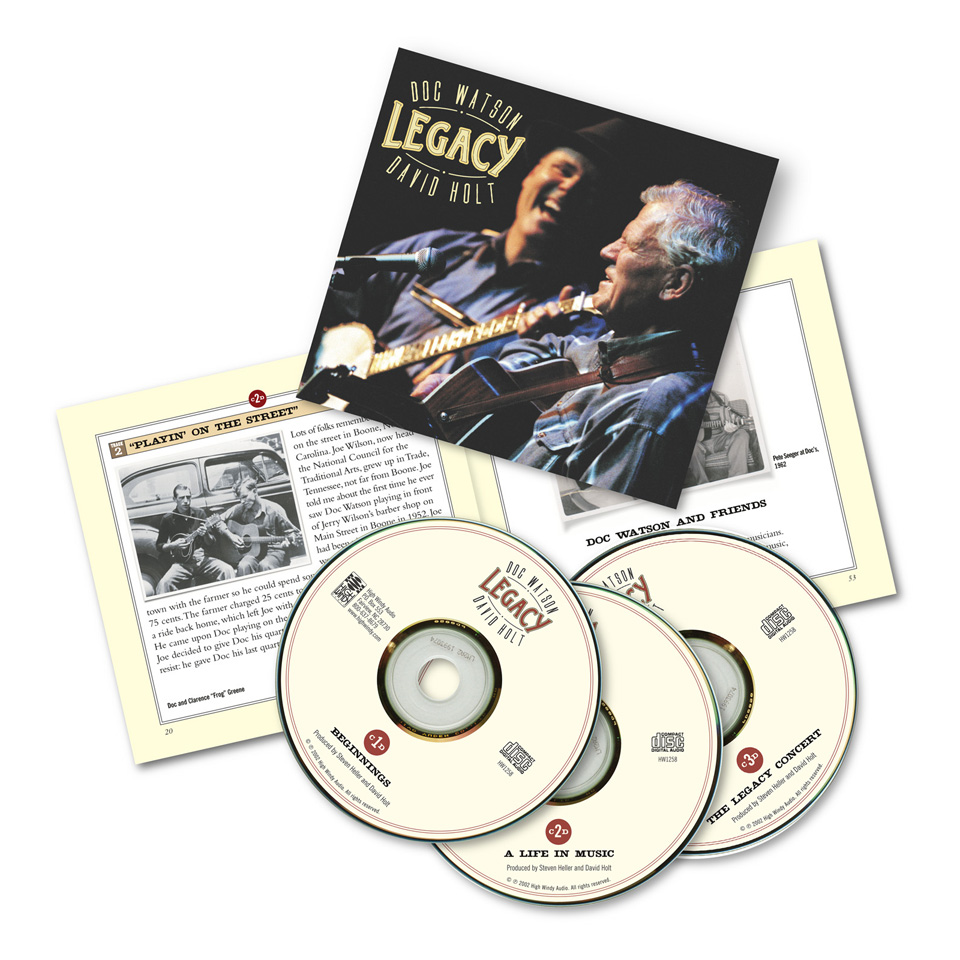

While fully acknowledging the old-man-cloud-yelling aspect of this position, I encourage you to find ways to pursue new customers or keep existing ones by gifting them something cool and engaging that’s well-printed on nice paper. I don’t mean workaday carryout menus/hangtags/rack cards. I mean something lavish and unnecessary—like any good gift. I’m asking both for the sake of a primal and liberating craft whose practioners didn’t deserve abandonment by the people paying for whatever passes as “marketing” today (shakes fist at cumulus). One day the presses rolled out beautiful, luxurious, tactile statements of superiority and community largess all varnished and diecut and perfect-bound and banded and boxed. The next day—poof!—everybody’s corporate corporeality had become perfectly, literally insubstantial. Don’t spend all your dough on electrons. Set aside some for ink. For the printers, lord bless them. And for old farts like me, for whom every screen is just another Vignelli grid in search of some 100C.

As I only consider myself a journeyman, not a master, here’s as far as I’ll go in wisdom-imparting on the subject of graphic design. First, if you are not an actual putting-food-on-the-table pro, please stay away from it. Don’t attempt it. I know it looks like fun (which it really isn’t), but you will fail at it. Ir’s ok. That’s why we’re here. Like your accountant, or your mechanic or the person who cuts your hair—none of whose jobs you would do yourself. The darkest day in our trade’s history was the one when the word “font” showed up on everyone’s computer screen. Before that day, no one who wasn’t in the priesthood knew what a font was, much less posess the wherewithall to access and toss about a limitless number of them in ordinary business, school, and personal communications. It was nothing short of terrifying. Going from typewriters to Macs was like handing tender, young, inexperienced drivers-ed students the keys to fire-breathing hot rods and then going back inside. Wanton destruction and chaos. When someone long ago aked me what I thought of this new-fangled Photoshop thing, I replied “mail-order guns.”

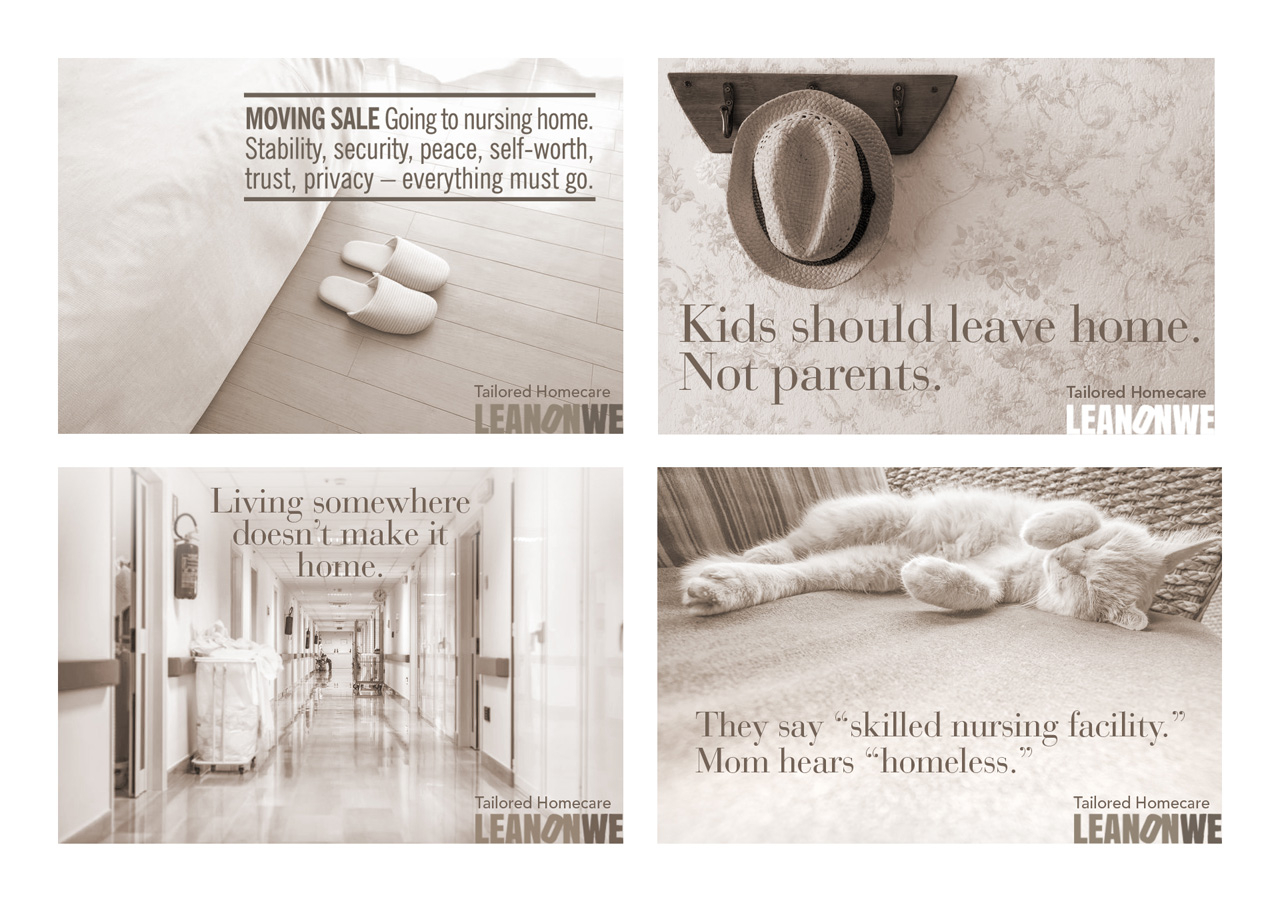

Don’t talk about what you have. Talk about what they want. I know it seems kind of counterintuitive; “I’m paying for this, so I’m by god gonna write about and photograph and livestream and feed you every drop-forged-hand-carved-whole-grain-eco-friendly-genuine-leather square inch of my product.” But believe me, people are far less interested in your product than in how owning your product will make them feel. Good advertising isn’t bragging. It’s empathizing.

“You see before you, Jeeves, a toad beneath the harrow.”

B. Wooster